and poultry and closely linked to processors (Hoppe and Korb, 2005).

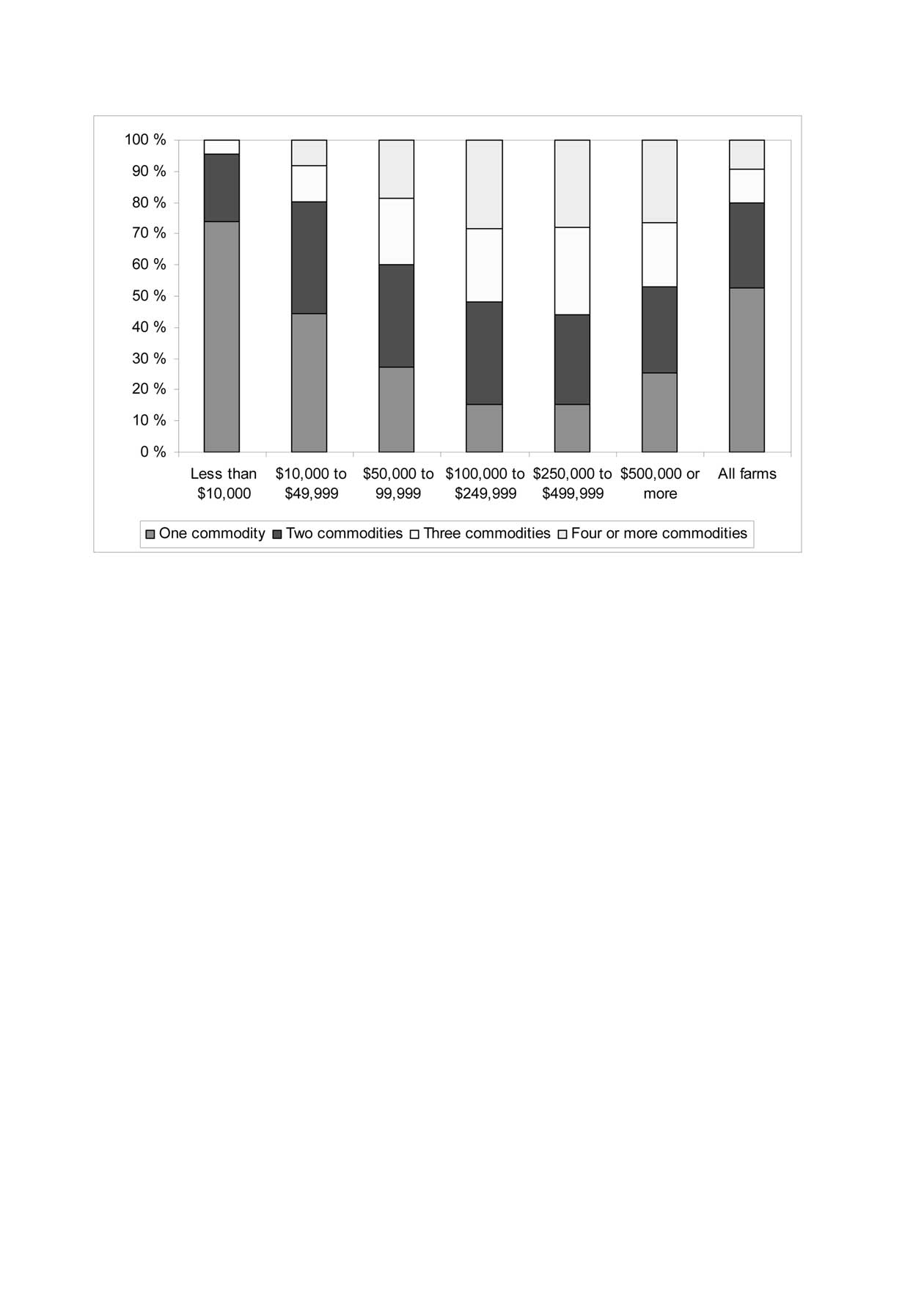

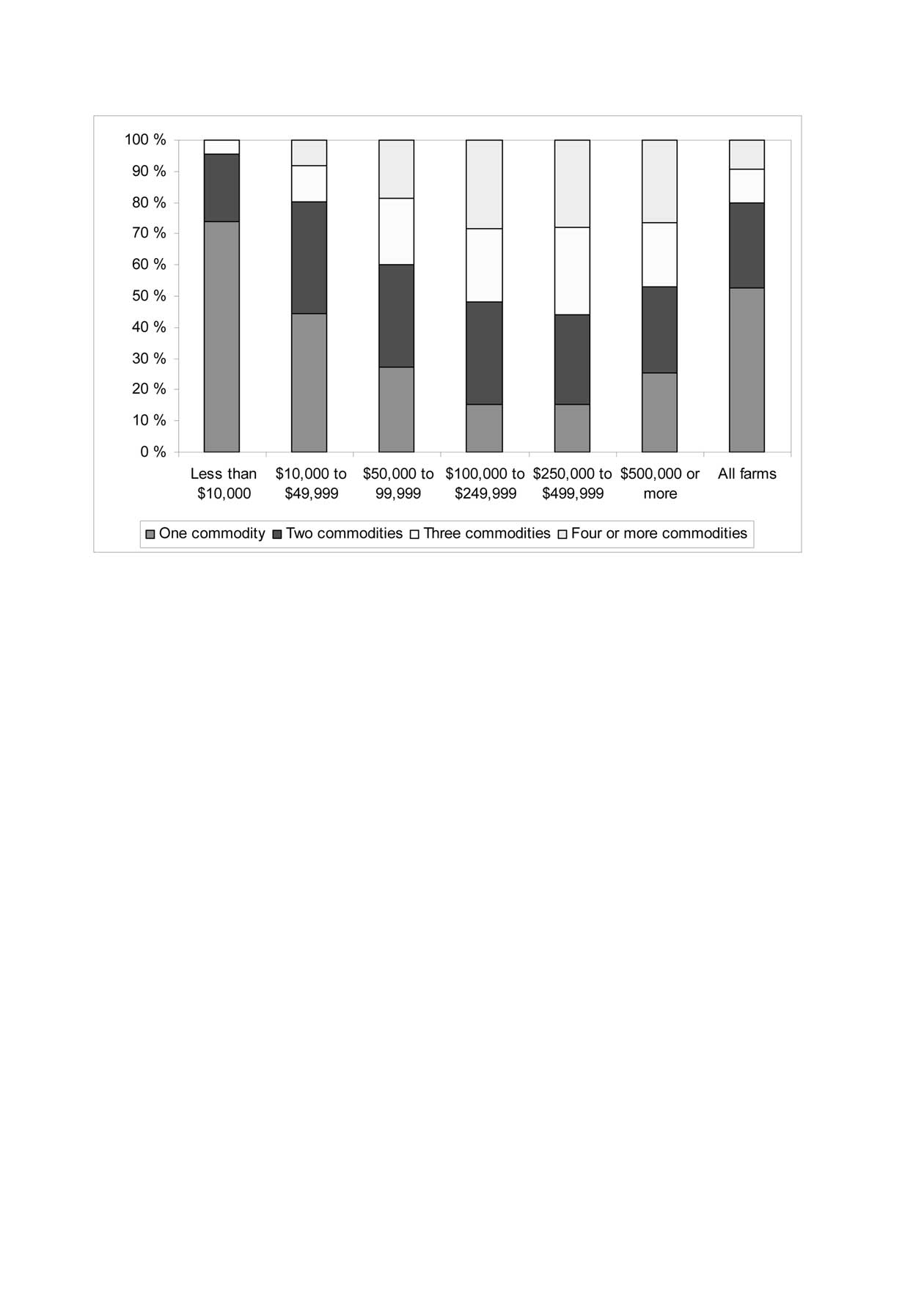

While agricultural production is now highly concentrated in large farms, there still are a large number of more diverse small farms coexisting with a small number of very large farms that capture most of the markets for agricultural commodities (Miljkovic, 2005). Crop diversity declined between the 1930s and 1980s; the area sown to grain crops increased and woodland on farms declined (Medley et al., 1995). During this period the number of farms decreased by 60% and farm size increased from 37 ha in 1925 to 72 ha in 1987.

An examination of farm by type of ownership-operation provides a useful look at the diversity of farm types currently in the US. Land is distributed fairly evenly among different types of farms, ranging from part-time farmers to very large scale operations (Figure 2-3). The large-scale, very-large-scale and non-family farms represent a disproportionately large fraction of the total US farm production (73% of the production from 38% of the farm area). Yet the majority of farms (98%) in the US as of 2003 are family-owned farms, though they may be organized as proprietorships, partnerships, or family corporations (Hoppe and Banker, 2006).

Specialization in the eastern part of NAE has followed a different path due to collectivization after World War II. The collectivization of agriculture was intended to exploit economies of scale, particularly in respect to mechanization and the use of agrichemicals. These were more obvious in large-scale crop production and possibly in intensive livestock production; they were less clearly applicable to farming in mountainous areas, or with labor-intensive crops. Collectivization led to the establishment of large collective or state farms which were highly mechanized and specialized but often inefficient in their use and allocation of resources. In the former Soviet Union the collectivized sector of agriculture (99.6% of agricultural producers were collectivized by 1955) grew significantly during the post-war de- |

|

cades (Matskevich, 1967). After World War II, the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries were major suppliers of agricultural products to the Soviet Union. Compared to the more arid regions of the Soviet Union, soils were relatively productive and a system of large collective farms were developed in the 1930s (Wheatcroft and Davies, 1994). This system was only economically viable under the centralized agricultural economies of the Socialist era.

As in the rest of NAE, the farm structure was dualis-tic in many CEE countries with numerous small self-subsistence plots and large-scale farms producing most of the gross output. Soviet agriculture essentially branched into two sectors. The collectivized sector was characterized by state-controlled, large-scale reliance on off-farm inputs, mechanization and hired labor and centralized processing and distribution of outputs. This sector was capital intensive and emphasized the management of quantities rather than qualities, because of the lack of price signals for quality, whether judged by processing enterprises or final consumers (Sharashkin and Barham, 2005). Moreover, there was widespread use of agronomic and veterinary expertise (sometimes located within individual farms), which led to the provision of improved varieties of crops and livestock. Collectivized farms were linked to centralized input-supply and product-processing facilities. The other branch of Soviet agriculture was the household-managed sector, characterized by micro-scale, lack of state support or inputs, manual labor provided by the household and self-provisioning goals (Sharashkin and Barham, 2005). The latter was authorized by Soviet authorities at the beginning of WWII to fight impending food shortages and quickly spread throughout the country (Lovell, 2003). This household-based sector continued to grow and by the mid-1950s accounted for 25% of the country's agricultural output (Wadekin, 1973). Throughout the Socialist period, the authorities maintained an ambivalent attitude toward household producers; their importance to food security was tacitly recognized, yet the government |