cerning technological change and the institutional landscape that will affect these livestock systems in the future (Freeman et al., 2006), the shifts in production to the wetter and mixed systems that are implied are likely to have considerable potential environmental impacts in the reference run.

Food trade, prices, and food security. Real world prices of most cereals and meat are projected to increase significantly in coming decades, reversing trends from the past several decades. Maize, rice, and wheat prices are projected to increase by 21-61% in the reference world, prices for beef and pork by 40% and 30%, respectively, and for poultry and sheep and goat by 17% and 12%, respectively (Table 5-10). These substantial changes are driven by new developments in supply and demand, including much more rapid degradation on the food production side, particularly as a result of rapidly growing water scarcity, rapidly growing demands, both food and nonfood, combined with slowing yield growth unable to catch up with developments on the supply and demand side.

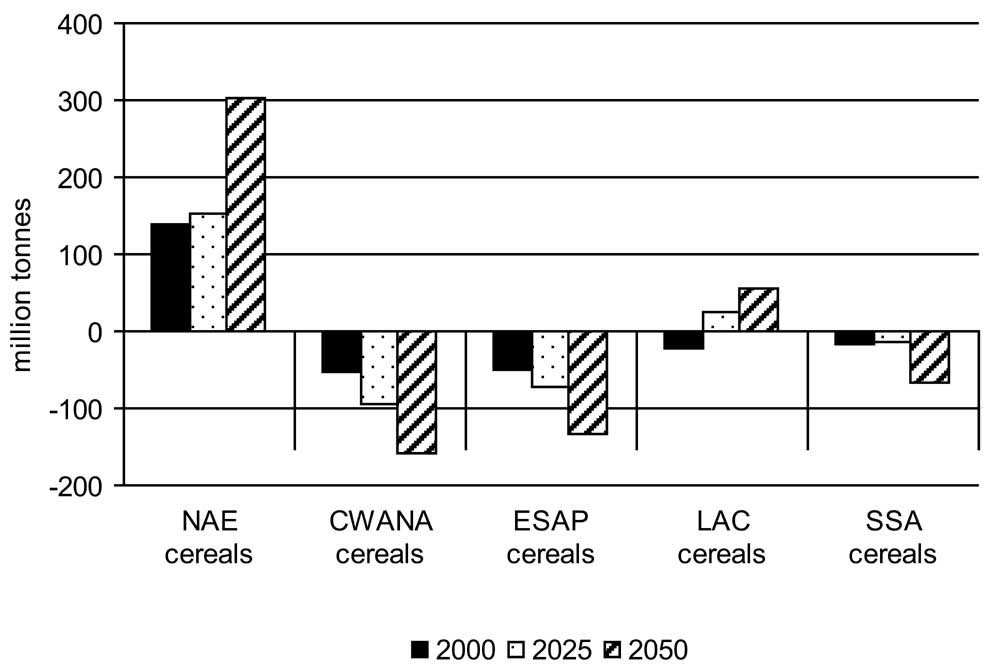

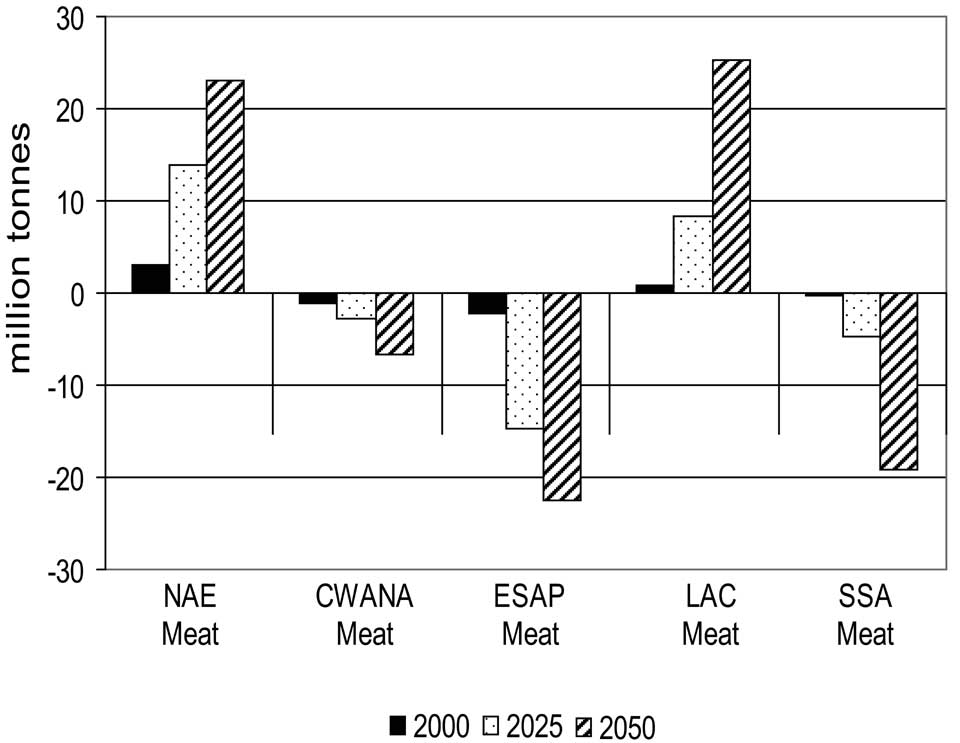

World trade in food will continue to increase, with trade in cereals projected to increase from 257 million tones annually in 2000 to 657 million tonnes in 2050 and trade in meat products rising from 15 million tonnes to 62 million tonnes. Expanding trade will be driven by the increasing import demand from the developing world, particularly CWANA, ESAP, and SSA, where net cereal imports will grow by 200%, 170%, and 330%, respectively (Figure 5-6). Thus, sub-Saharan Africa will face the largest increase in food import bills despite significant area and yield growth expected during the next 50 years in the reference world.

With rising prices due to the inability of much of the developing countries to increase food production rapidly enough to meet growing demand, the major exporting countries—mostly in the NAE and LAC regions—will provide an increasingly critical role in meeting food consumption needs (Figures 5-6 and 5-7). The USA, Brazil, and Argentina are a critical safety valve in providing relatively affordable food to developing countries. Maize exports are expected

Table 5-10. Selected international food prices, 2000 and projected 2025 and 2050, reference run.

| 2000 | 2025 | 2050 | |

| Food | US$ | per metric ton | |

| Beef | 1,928 | 2,083 | 2,691 |

| Pork | 878 | 986 | 1,142 |

| Sheep & goat | 2,710 | 2,685 | 3,039 |

| Poultry | 1,193 | 1,192 | 1,399 |

| Rice | 191 | 223 | 232 |

| Wheat | 99 | 136 | 160 |

| Maize | 72 | 108 | 102 |

| Millet | 227 | 293 | 289 |

| Soybean | 186 | 216 | 216 |

Note: All values are three-year averages. Source: IFPRI IMPACT model simulations.

Figure 5-6. Net trade in cereals, reference run, by IAASTD region. Source: IFPRI IMPACT model simulations.

to double in the United States to 102 million tonnes, and to grow to 38 million tonnes in Argentina and 10-11 million tonnes in Brazil and Mexico. Wheat exports are projected to grow to 60 million tonnes in the United States, and to 37 million tonnes in Russia, 34 million tonnes in Australia, and 31 million tonnes in Argentina, respectively. Soybean exports are projected at 20 million tonnes in Argentina and 15 million tonnes in Brazil. Net meat exports are expected to increase sharply in the United States and Argentina. Europe is expected to also increase exports, mainly because of slow or no growth in demand with stable population. For rice, Myanmar is expected to join Thailand and Vietnam as particularly significant exporters.

The substantial increase in food prices will slow growth in calorie consumption, with both direct price impacts and reductions in real incomes for poor consumers who spend a large share of their income on food. As a result, there will be little improvement in food security for the poor in many regions. In sub-Saharan Africa, daily calorie availability is

Figure 5-7. Net trade in meat products, reference run, by IAASTD region. Source: IFPRI IMPACT model simulations.