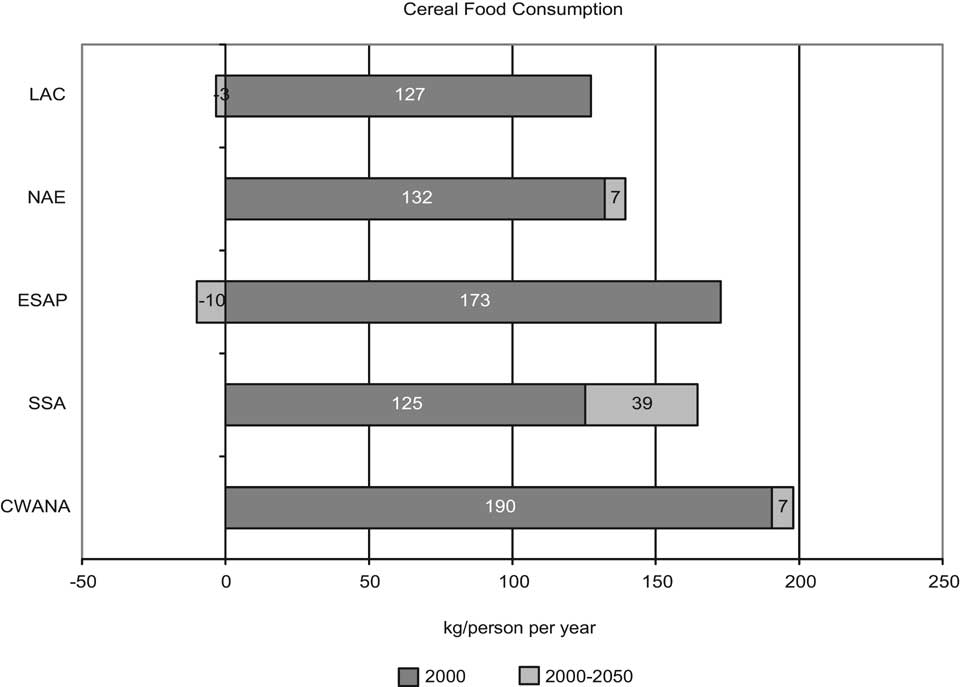

Figure 5-2. Per capita availability of cereals as food, 2000 and 2050, reference run, by IAASTD region. Source: IFPRI IMPACT model simulations.

from 1.7 billion in 2000 to 2.7 billion in 2050, again with substantial increases in all regions except NAE. In ESAP, sheep and goat numbers are increasing to 2050 still, but the rate of increase is declining markedly. In all other regions, numbers reach a peak sometime around 2040, and then start to decline. Globally, pig numbers are expected to peak around 2030 and then start to decline, and numbers in no region are projected to increase between 2040 and 2050. Poultry numbers are projected to more than double by 2050. Peak numbers are reached around 2045 in NAE, with small declines thereafter, while numbers are continuing to increase somewhat in CWANA and SSA and still rapidly in LAC and ESAP. Growth in cereal and meat consumption will be much slower in developed countries. These trends are expected to lead to an extraordinary increase in the importance of developing countries in global food markets.

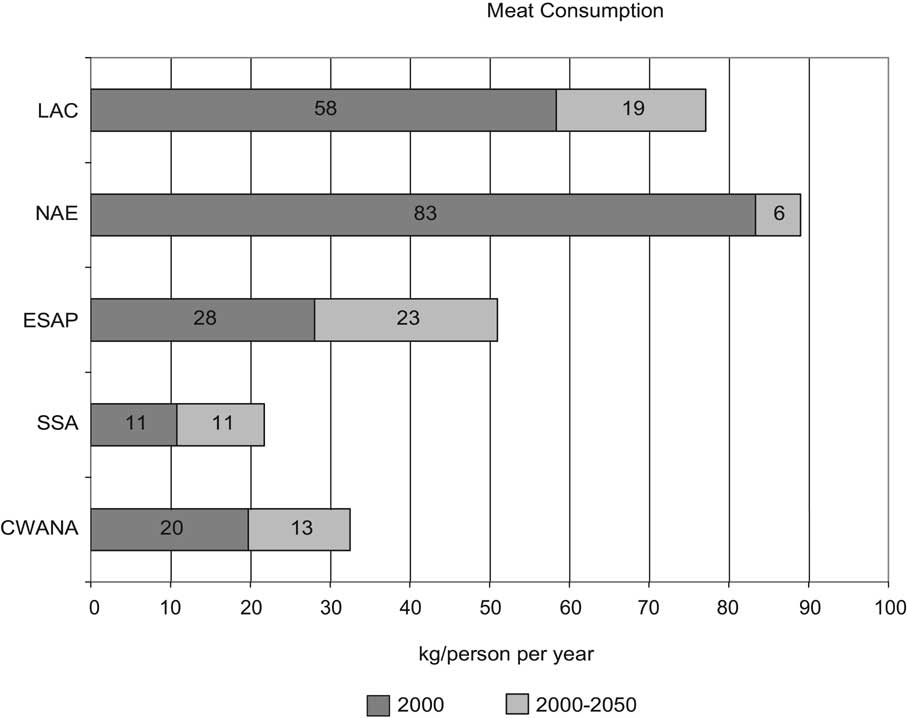

Figure 5-3. Per capita availability of meats, 2000 and 2050, reference run, by IAASTD region. Source: IFPRI IMPACT model simulations.

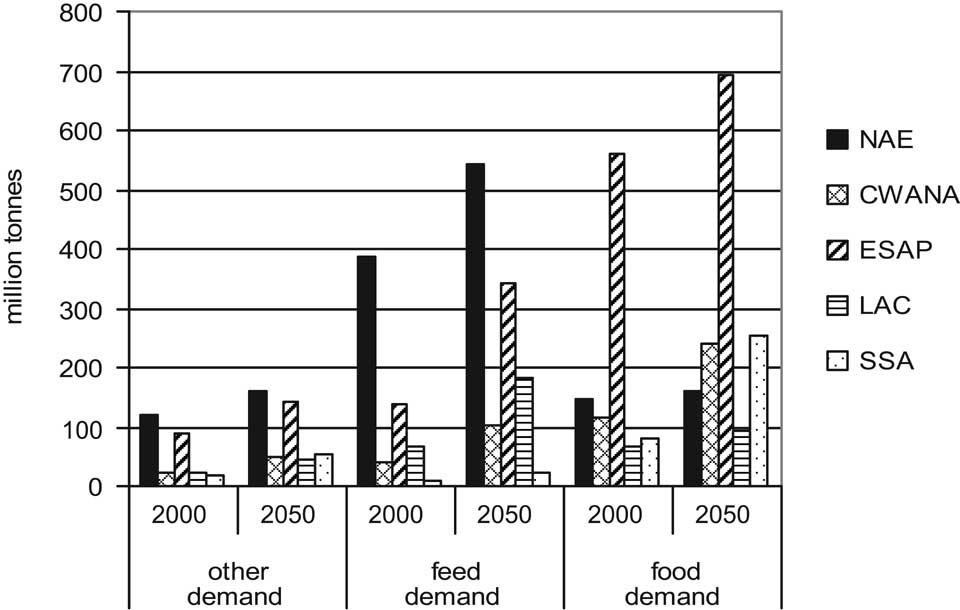

Figure 5-4. Cereal demand as feed, food & other uses, 2000 and projected 2050, reference run, by IAASTD region. Source: IFPRI IMPACT model simulations.

Sources of food production growth. How will the expanding food demand be met? For meat in developing countries, increases in the number of animals slaughtered have accounted for 80-90% of production growth during the past decade. Although there will be significant improvement in animal yields, growth in numbers will continue to be the main source of production growth. In developed countries, the contribution of yield to production growth has been greater than the contribution of numbers growth for beef and pig meat; while for poultry, numbers growth has accounted for about two-thirds of production growth. In the future, carcass weight growth will contribute an increasing share of livestock production growth in developed countries as expansion of numbers is expected to slow. For the crops sector, water scarcity is expected to increasingly constrain production with virtually no increase in water available for agriculture due to little increase in supply and rapid shifts of water from agriculture in key water-scarce agricultural regions in China, India, and CWANA (see water resources discussion below). Climate change will increase heat and drought stress in many of the current breadbaskets in China, India, and the United States and even more so in the already stressed areas of sub-Saharan Africa. Once plants are weakened from abiotic stresses, bi-otic stresses tend to set in and the incidence of pest and diseases tends to increase. With declining availability of water and land that can be profitably brought under cultivation, expansion in area is not expected to contribute significantly to future production growth. In the reference run, cereal harvested area expands from 651 million ha in 2000 to 699 million ha in 2025 before contracting to 660 million ha by 2050. The projected slow growth in crop area places the burden to meet future cereal demand on crop yield growth. Although yield growth will vary considerably by commodity and country, in the aggregate and in most countries it will continue to slow down. The global yield growth rate for all cereals is expected to decline from 1.96% per year in 1980-2000 to 1.02% per year in 2000-2050; in the NAE