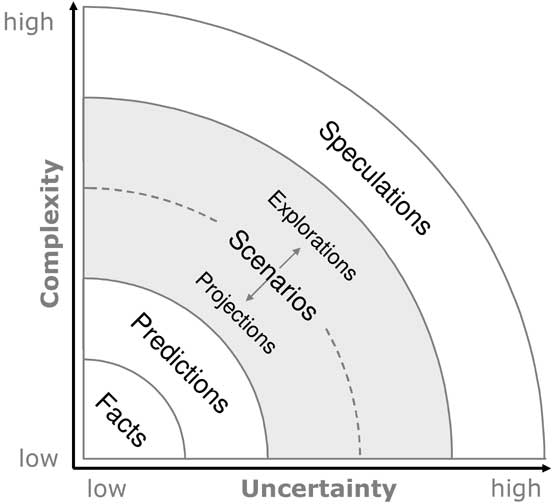

Figure 4-2. Complexity and uncertainty associated with forward-looking assessments. Source: Zurek and Henrichs, 2007.

prospects for agricultural science, technology and knowledge (AKST) in much detail. Nevertheless, these assessments still provide important sources of information for discussing future developments underpinning agriculture and the role of AKST. In general, assessments are helpful in exploring possible development pathways for the most important drivers and their interactions. However, assessments are limited by the ranges of key scenario inputs they consider. For example, crop production has abruptly increased in the past few years (driven by demand for biofuels and increased food demand) with prices of some crops doubling. These price increases clearly exceed the range in price projections in existing assessments. Hence, although assessments are helpful in assessing interaction forces in terms of direction of change, they need to be treated carefully as they poorly capture abrupt changes falling outside the range of modeled scenarios.

Assessments of particular relevance for the IAASTD include a wide range of exercises—some of which focus on agriculture, while others address agricultural development within the context of other issues. These assessments can be roughly grouped in two categories: Projection-based studies (which commonly set out to present a probable outlook or best estimate on expected future developments) and exploratory studies (which develop and analyze a range of alternative scenarios to address a broader set of uncertainties) (Box 4-1).

Prominent examples of projection-based assessments of direct relevance to IAASTD include the FAO's World Agriculture 2030 (Bruinsma, 2003) and IFPRI's World Food Outlook (Rosegrant et al., 2001). Important examples of recent international assessments that explore a wider range alternative scenarios include the global scenarios discussed by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA, 2005a), UNEP's Global Environment Outlooks (UNEP 2002, 2007; RIVM/UNEP 2004), IPCC's Scenarios as used in Third and

Fourth Assessment Reports (IPCC 2001, 2007abc) and the Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture (CA, 2007).

Most of the above mentioned assessments have either focused on informing sustainable development in general or addressed crosscutting environmental issues. Only two global scale assessments (i.e., IFPRI and FAO) have focused on projecting future agricultural production (yet even these have not addressed the full spectrum of agrarian systems and AKST from the perspective of a range of different plausible futures) (Table 4-1). It should be noted that, in addition, a range of national or regional projections of agricultural production and food security exists, but will not be discussed here.

All of the international assessments highlighted above have identified detailed assumptions about the future developments of key driving forces and reflected on a number of underlying uncertainties about how the global context may change over the coming decades. While the number of uncertainties about plausible or potential future developments is vast, a limited number of key uncertainties seem to reappear in several recent international assessments. This is well illustrated by looking at a few "archetypical" scenarios (see Raskin, 2005; van Vuuren, 2007). These scenario archetypes not only share the perspective on key uncertainties about future developments, but as a result also have similar assumptions for different driving forces (Table 4-2, 4-3): Economic optimism/conventional markets scenarios: i.e., scenarios with a strong focus on market dynamics and economic optimism, usually associated with rapid technology development. Examples of this type of scenario include the A1 scenario (IPCC), the Markets First scenario (UNEP) or the Optimistic scenario (IFPRI). Reformed Market scenarios: i.e., scenarios that have a similar basic philosophy as the first set, but include some additional policy assumptions aimed at correcting market failures with respect to social development, poverty alleviation or the environment. Examples of this type of scenario includes the Policy First scenario (UNEP) or the Global Orchestration scenario (MA). Global Sustainable Development scenarios: i.e., scenarios with a strong orientation towards environmental protection and reducing inequality, based on solutions found through global cooperation, lifestyle change and more efficient technologies. Examples of this type of scenario include the B1 scenario (IPCC), the Sustainability First scenario (UNEP) or the TechnoGarden scenario (MA). Regional Competition/Regional Markets scenarios; i.e., scenarios that assume that regions will focus more on their more immediate interests and regional identity, often assumed to result in rising tensions among regions and/or cultures. Examples of this type of scenario include the A2 scenario (IPCC), the Security First scenario (UNEP), the Pessimistic scenario (IFPRI) or the Order from Strength scenario (MA). Regional Sustainable development scenarios: i.e., scenarios, that focus on finding regional solutions for current environmental and social problems, usually combining drastic lifestyle changes with decentralization of governance. Examples of this type of scenario include the