| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||

Context, Conceptual Framework and Sustainability Indicators | 29

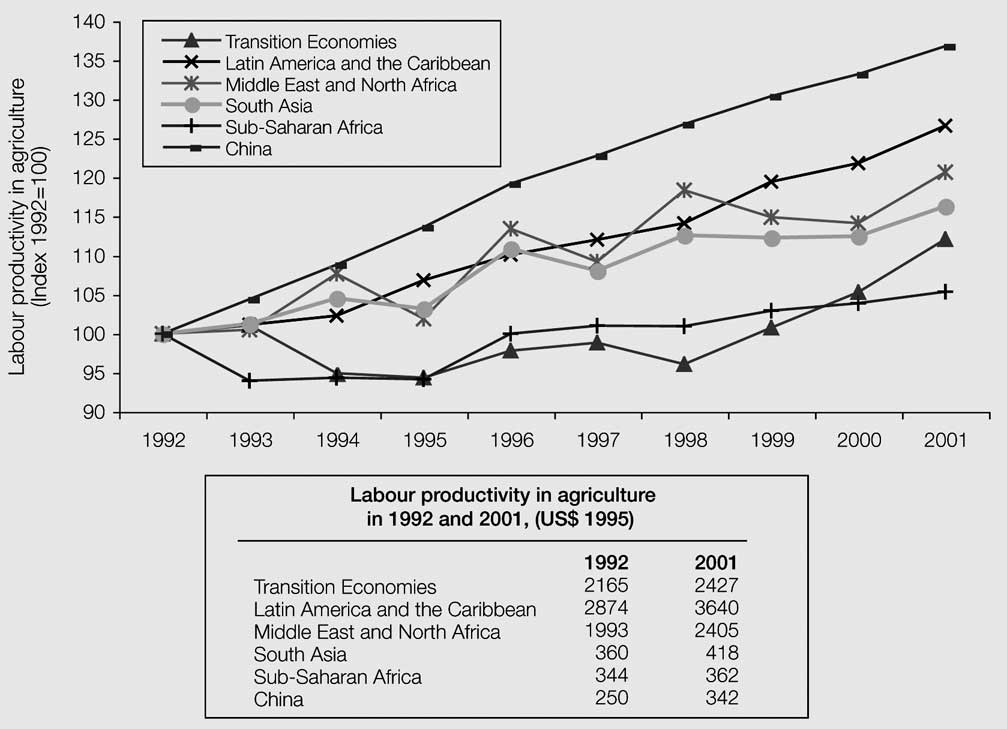

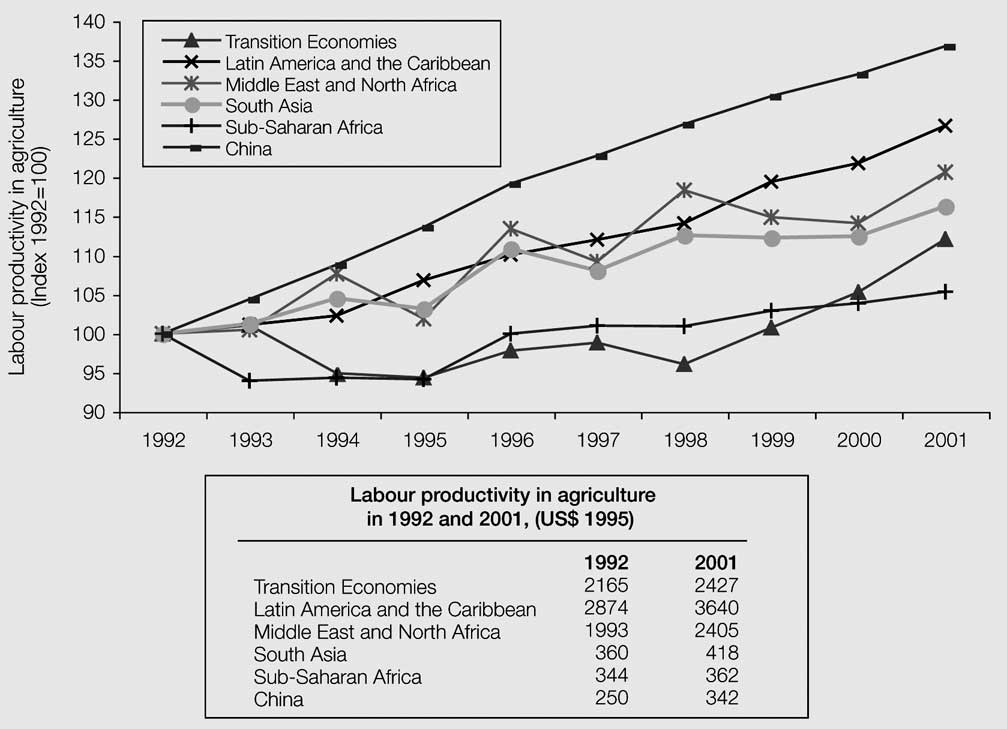

Figure 1-14. Labor productivity in agriculture by region (1992-2001) and labor productivity levels in 1992 and 2001. Source: ILO, 2004

|

fucountries as were published by authors from developing countries in 2001 (World Bank, 2006c). Measurement of the different forms of capital poses many challenges, particularly for those forms that are nonmarketed. In an effort to better understand the importance of different types of capital, the World Bank (1997) undertook to estimate the value of human resources, produced assets, and natural capital. They noted that human resources include both raw labor power and the embodied knowledge that comes from education, training and experience. Monetary values are admittedly imprecise, but what was striking about their results was the uniform dominance of human resources, which accounted for 60-80% of total wealth in all regions except for the Middle East, where natural capital, in the form of energy reserves, accounted for an unusually high proportion. Livelihoods, resilience, and coping strategies. Even though a large number of people depend entirely on agriculture, offfarm income is important for the livelihoods of many farming households. Agriculture's share of GDP was declining in both developing and high-income countries, while the share accounted for by the service sector was increasing-to 52% in developing countries and 72% in high-income countries (World Bank, 2006c). Data are scarce, but in many developing countries the informal sector accounts for a large (and in some cases rising) share of urban employment (World Bank, 2006c). Remittances from workers abroad form an increasing share of income in most developing regions, totaling US$161 billion in 2004 and accounting for more than 3% of GDP in South Asia (World Bank, 2006c). A household may be able to avoid hunger and maintain its human capital during a drought by depleting its financial, physical |

or natural capital (for example, by drawing on its savings or selling its livestock or failing to maintain the fertility of its soils). But this may threaten its ability to survive over the longer term. Alternatively, a household may accept severe cuts in consumption in the short term, with consequences for health and strength, precisely in order to protect its endowment of other resources and its ability to recover in future. Different resource endowments and different goals imply different incentives, choices, and livelihood strategies. For example, two households that have the same endowments of land, labor, and materials may choose different cropping strategies if one household does not have access to savings, credit or insurance and the other one does. In this case the first household may choose to plant a safe but lowyielding crop variety while the second household will plant a riskier variety-expecting higher yields while at the same time knowing that additional financial capital could help sustain income (and consumption levels) even if it were to suffer a poor harvest. Likewise different livelihood strategies and different weather and market conditions imply different outcomes, which in turn imply different endowments. In the example just mentioned, the first household may suffer smaller losses in a drought year, but also smaller gains in average and good years. Even when both households suffer losses, their coping strategies might differ. The first, in order to meet consumption needs, might be forced to sell assets. If many other households are in a similar position, asset prices might fall, making it even more difficult to exchange them for sufficient food. Households with sufficient food or financial reserves, by contrast, may be in a position to buy assets at discounted prices, increasing not only their own ability to survive fucountries |

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||