widespread declines in the populations of many groups of organisms associated with farmland (e.g., arable plants, invertebrates, farmland birds) since the 1940s in Britain and North-West Europe. A review of 18 studies investigating changes in wildlife in arable farmland in Great Britain confirmed the decline of many taxa. In only two studies (on butterflies) was there evidence of an increase over the survey periods (Robinson and Sutherland 2002). Similar results have been found in Portugal (Stoate et al., 2001).

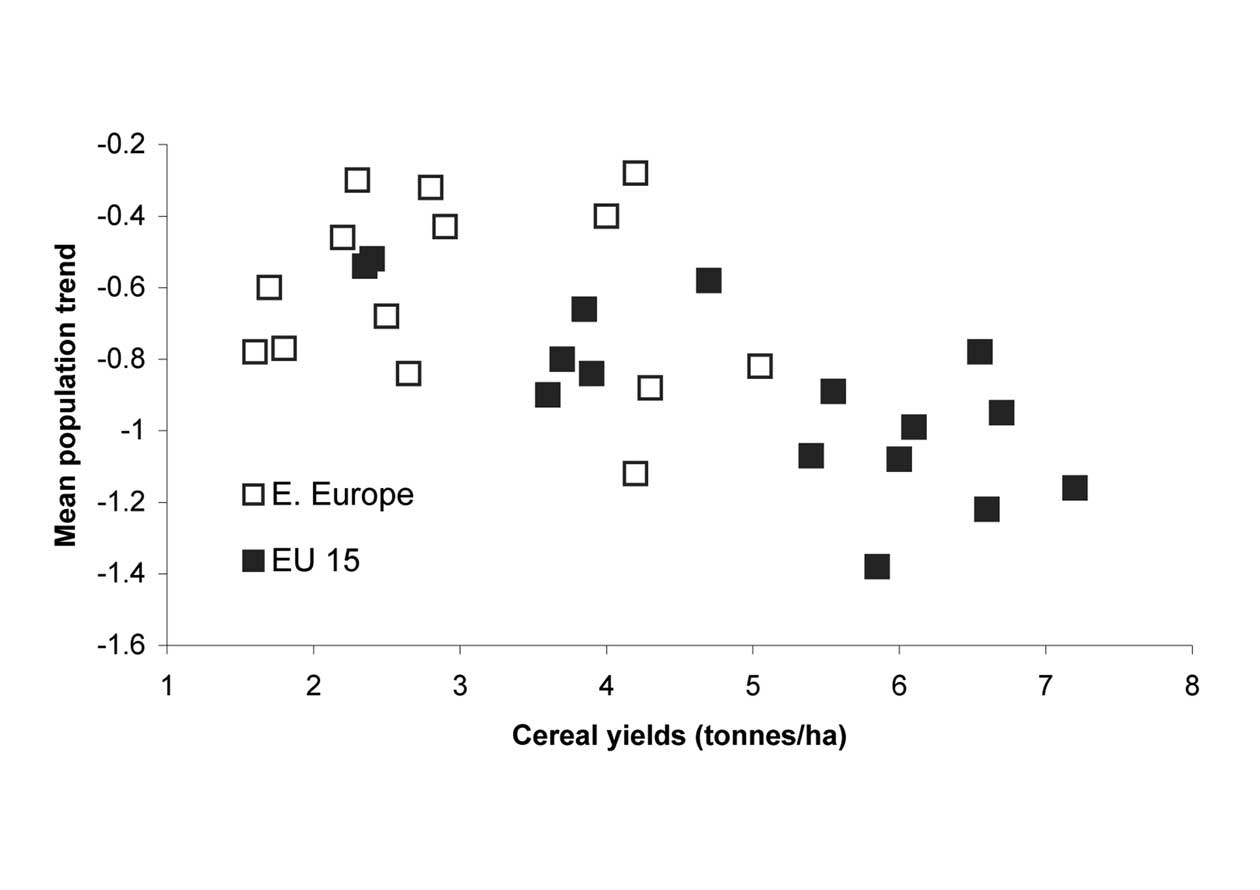

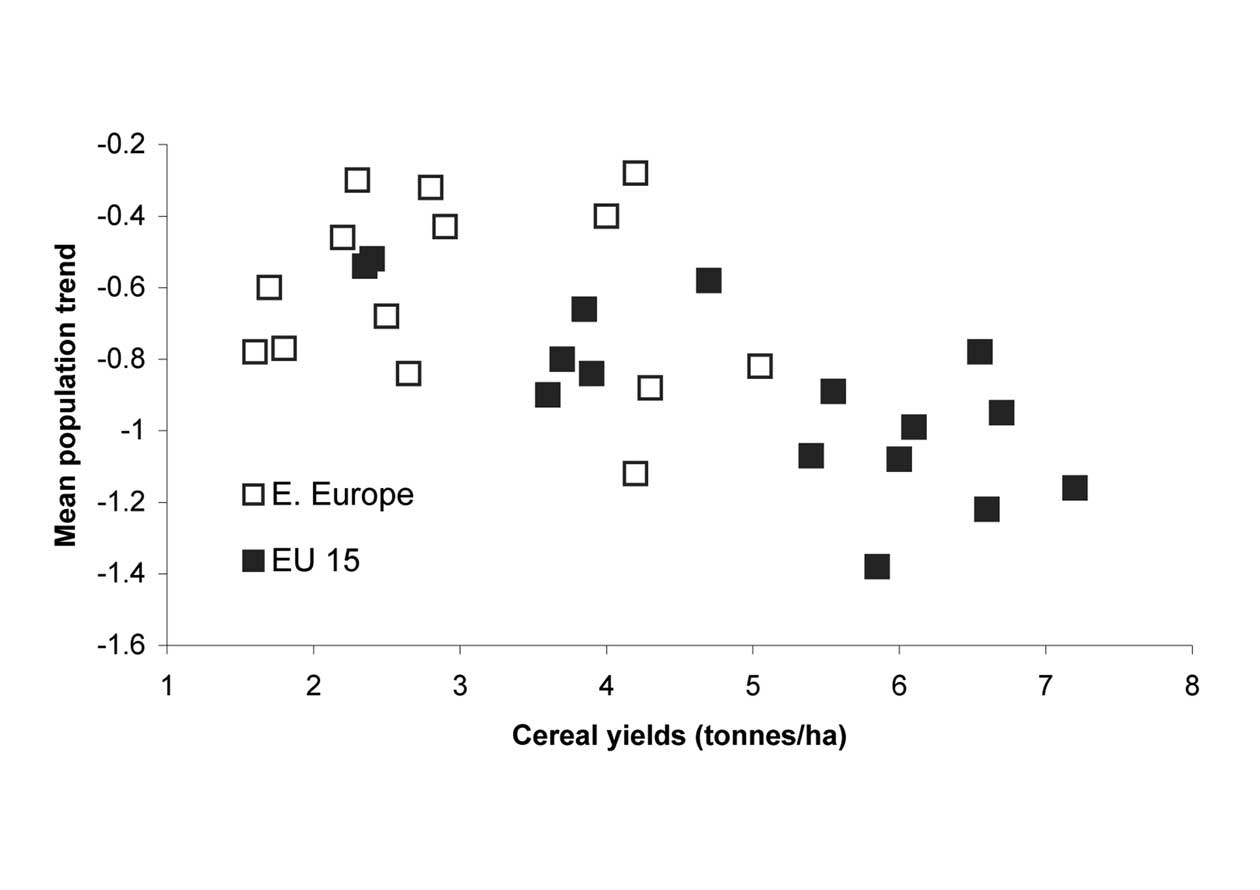

At a wider European level, decline in farmland bird populations have been related to agricultural "intensity" (Donald et al., 2002). At its simplest there is a link between average cereal yields (FAOSTAT) and the rate of bird decline (Figure 3-3). A similar study on invertebrates has reported on changes in bees and hoverfly populations in Britain and the Netherlands pre and post 1980, concluding that there has been a decline in bee diversity in most of the assessed areas in both countries since 1980 (Biesmeijer et al., 2006). This decline seemed to be linked to declines in pollinator plants, which may well have become less common as a result of agricultural intensification (Preston et al., 2002). The overall conclusion for Europe, east and west, is that increased farming intensity over the last 50 years, although leading to appreciable increases in production per unit area, has had a negative impact on the environment and ecosystem services (Tilman, 1999). A further complicating issue relates to the impact of land abandonment in some areas of East and Southern Europe on biodiversity. Economic pressures have resulted in fields not being farmed and as a consequence scrub has started to invade, degrading the habitats' suitability for many farmland species, though it does increase its suitability for others.

Concerns about the impact of food production on ecosystem services loom less large in North America, although American-based ecologists are as concerned as European scientists about the impact of agriculture on the ecosystem (Tilman, 1999). Agriculture has a much smaller "footprint" in North America, as in the USA it uses less that 50% of the land surface and in Canada less than 10% (FAOSTAT, 2006). In general, management strategies of US natural resources have moved toward land or ecological-based systems |

|

which recognize the important role of the soil (Robertson et al., 1999). There has also been a changing philosophy to rangeland management in the US over the last 50 years (Orr, 2006) with management evolving from purely grazing objectives, to a more scientific approach, recognizing the need for "resource rehabilitation, protection and management for multiple objectives including biological diversity, preservation and sustainable development for people" (Stoddart et al., 1975; Heady and Child, 1994). Despite this changed philosophy more than one-half of all US rangeland ecosystems have lost 98% of pre-settlement flora, to agricultural use. The amount of US grazing land and rangeland is expected to continue to decline slowly over the next 50 years, as the land use shifts away from grazing use but there is no indication that endangered rangeland ecosystem types are being lost except for desert grasslands.

The decline of biodiversity can be at least partly attributable to the changes in farming systems which advances in agricultural technology have made possible. These include:

• The widespread use of pesticides has affected non-target species

• The development of machinery capable of establishing crops on soils not previously amenable to crop production has caused a decline in natural and semi-natural habitats

• The increased size of machinery, aimed at increasing efficiency, has resulted in field amalgamations and losses of hedges and other semi-natural wildlife habitats

• Simplification of rotations so that only a limited number of crops are grown, has decreased the planting of those with different biology and planting times, that formerly provided a greater range of habitats for wildlife

• The replacement of hay crops by the earlier harvested silage, for intensive animal production has reduced the environmental value of grasslands

Such technologies have typically been adopted by farmers after weighing the complex tradeoffs, economic and environmental, inherent in each. However, AKST is also continuing to provide newer and better tools and expertise to assess impacts of agricultural changes on wider biodiversity |