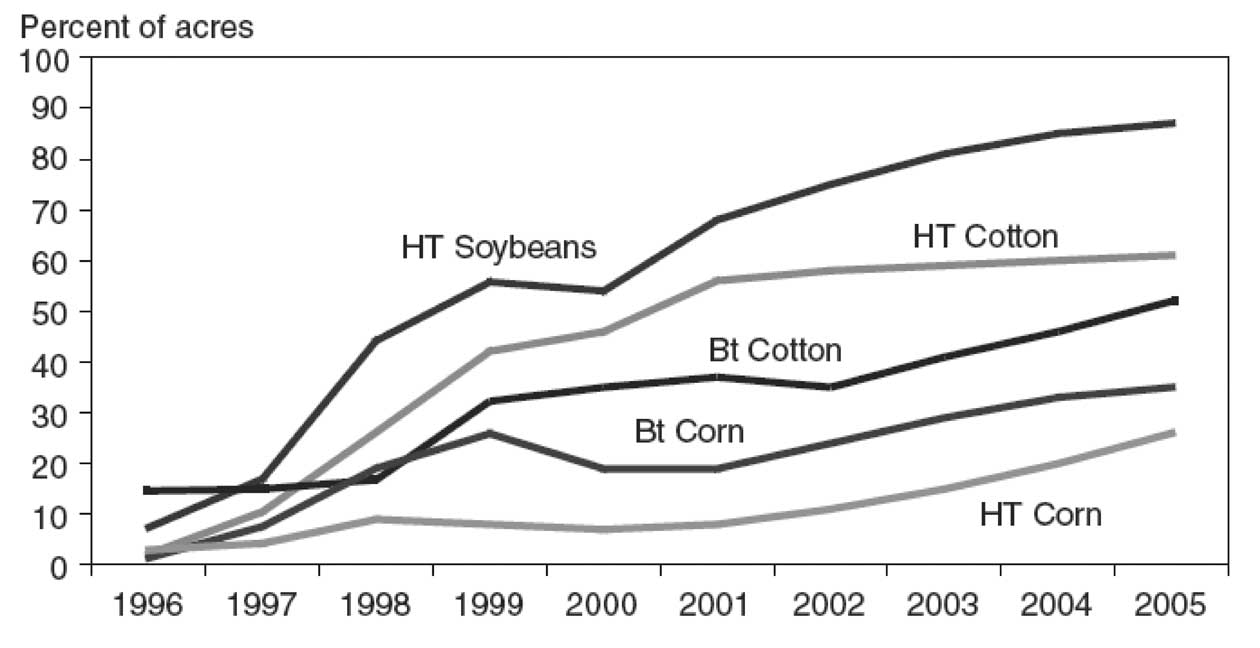

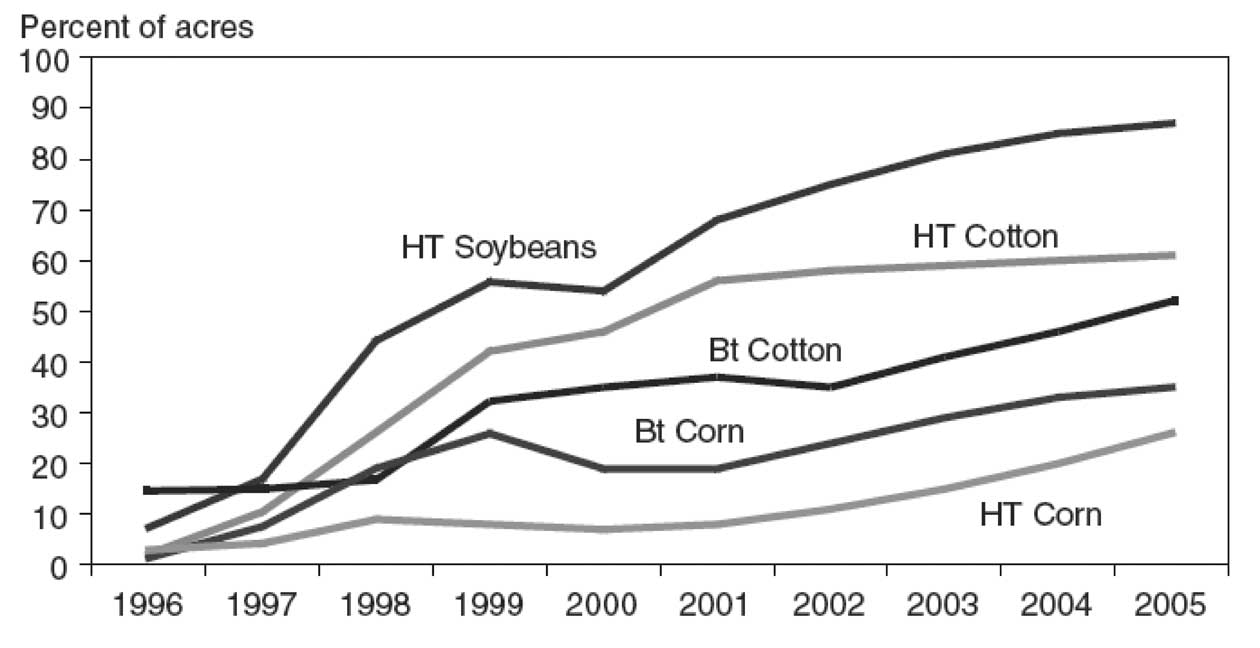

indicated that they did so mainly because of improved weed or pest control. Other reasons for adopting these varieties were to save management time, to make other practices easier and to decrease pesticide costs. The actual impact on farm income appears to vary from crop to crop; in some instances, management time savings have offered farm families the opportunity to generate more off-farm income (Fernandez-Cornejo and Caswell, 2006). In the EU, the total area of commercially grown GE crops is much less, accounting for only a few percent of the total maize harvest which is only grown for animal feed (GMO Compass, 2007). Regulatory differences and differences in public attitudes towards GE are the keys to understanding the different patterns of growth and are discussed later in this section.

Changes in the organizational arrangements of seeds and genetics

Plant breeders turned to new genetic techniques for a variety of reasons, including major emphasis on increased production and productivity in the political arena across the whole of NAE as well as because of market demand—c.f. discussion of political emphasis on demand in Eastern Europe (Medvedev, 1987). Moreover, efficient and well-financed knowledge transfer systems (e.g., extension and private consultants) moved these new plant breeding technologies and techniques into widespread use. In addition, plant breeders were responding to the larger scientific arena that was pushing knowledge boundaries.

Such major transformations in technologies and techniques were accompanied by significant changes in the organizational arrangements of seeds and genetics. Even as hybrid maize was developed by public institutes such as USDA in the 1920s, it became clear that there was an economic dimension to their development (Kloppenburg, 1991). Because the grain harvested from hybrid plants cannot produce economically viable seed, the seed has to be bought each year by the farmer. This contrasts with open pollinated varieties where seeds can be saved from year to year. Thus, the seed business developed from a public service to a profit- |

|

able industry (Fernandez-Cornejo, 2004). At the same time, the number of varieties researched, developed and produced by public institutes waned.

A major driver of the shift from public to private research was the establishment of Plant Breeders' Rights (PBR). PBR are granted to the breeder of a new variety of plant to grant the control of the seed of a new variety and the right to collect royalties for a number of years. For several of the main commodity crops, farmers cannot sell the seed they produce but can use their own crops as seed. In 1961, the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, which restricted the sale of propagated protected varieties, was signed. Within Western Europe and the United States, national legislation was passed in the 1960s and early 1970s in accordance with the Convention. The WTO's Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) and The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants regulate plant breeders' rights internationally.

The legislation concerning plant breeders' rights was intended to stimulate private investment in producing new varieties. It certainly has done this but some maintain that there is conflict between these international agreements on plant breeders' rights and the Convention on Biological Diversity which advocates "fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources. This has led to considerable continued discussion in a number of international forums. These uncertainties affect farmer practice and farmer profitability; clarification will be important for farmers in poor parts of the world to maintain profitability. The latter is important as the development of plant breeding techniques within NAE has had significant impacts on the rest of the world, particularly as many of these techniques and their resulting products have been transferred globally.

The way GE crops have been introduced into farming in NAE has in part depended on changes within agrochemical and seed industries. In the mid-1980s a new "technological trajectory" based on biotechnology began to emerge for |