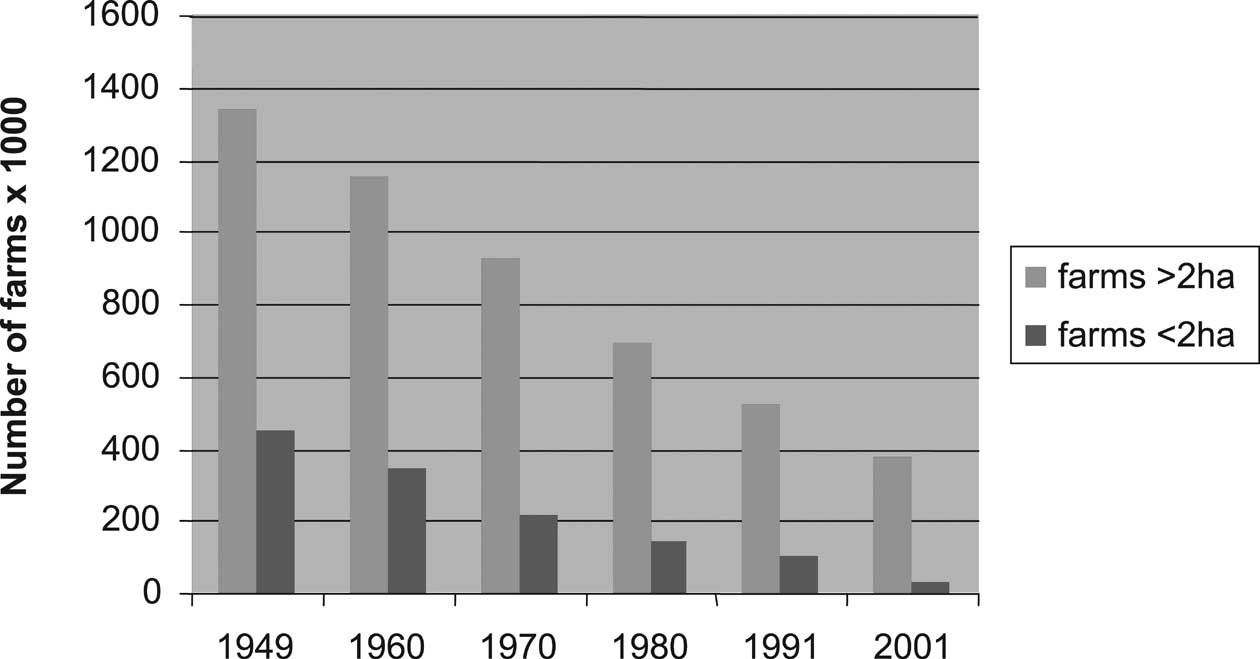

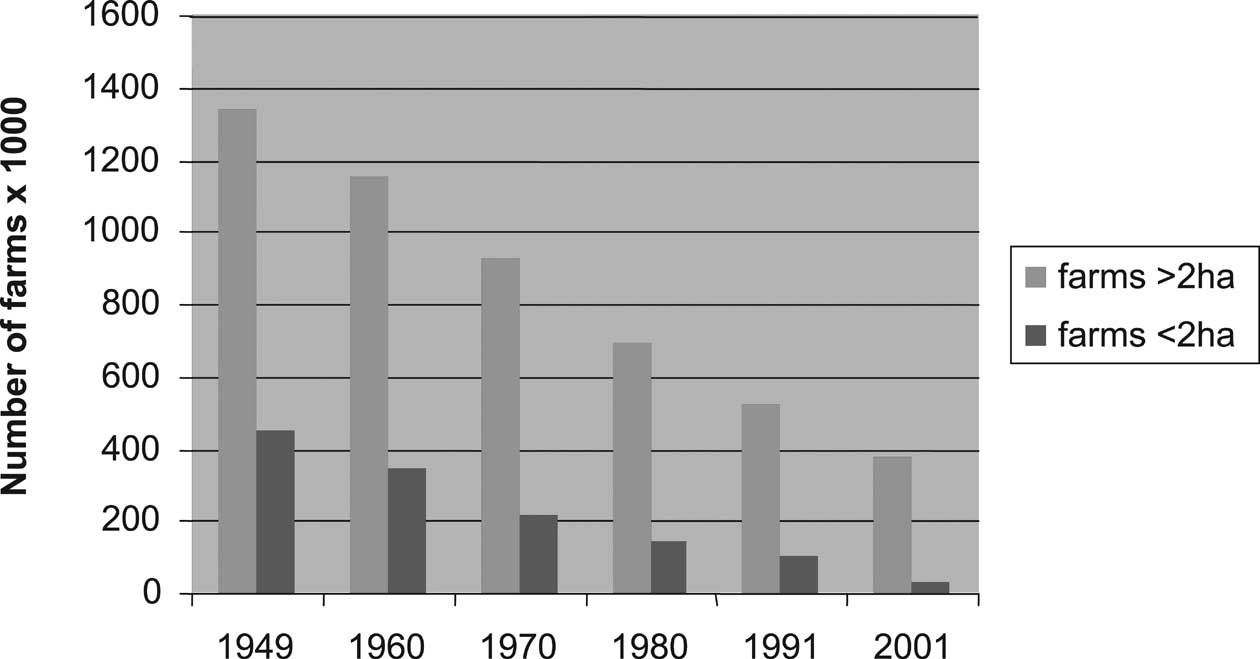

advanced during the following 50 years the number of farms and the number of farmers and farm workers has declined dramatically. In West Germany, for example, large farms (i.e., those over 2 ha) have declined from over 1,000,000 to less than 400,000, while the number of "small farms", mainly run by part-time farmers has declined even more dramatically. At the same time the area of farmed land has only declined from 12.8 million ha in 1949 to 11.4 million ha in 2001 (Gov. Germany, 2006), indicating that there has been a dramatic increase in average farm sizes (Figure 2-5). In France the agricultural workforce declined from 8% to about 4% of the total working population in between 1977 to 1997. However, since the reform to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in 1992 this decline in Europe, both in agricultural employment and the number of farms, has slowed down as can be seen in the annual percentage changes in labor force. Different countries and different areas in those countries have followed this pattern since 1990 to varying extents.

The changes in the agricultural labor force differed greatly throughout Europe with a noticeable North-South divide. Southern European countries such as Spain and Portugal lost more than a third of their labor force between 1987 to 1997, while the average for the European Community was a 25% reduction. This more dramatic decline reflects the fact that these southern Member States traditionally have a more labor-intensive Mediterranean style of agricultural production; approximately 9% of jobs in countries with Mediterranean production systems were associated with farming. Greece has a particularly high rate agricultural employment (about 20%). Northern European countries such as Denmark and the UK showed average agricultural employment figures closer to 3% for 1997.

In western Europe, individual national migration policy has been gradually subsumed under general EU agreements, although as exemplified by the expansion of the Union to 27 members, full legal labor mobility for citizens of EU states may be delayed and circumscribed by a number of local national regulations. The UK, for example, has developed |

|

regulations (e.g., the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme: SAWS) that respond to the need to attract farm workers for seasonal and temporary employment, building on a long history of dependence on migrant workers both from within and outside the UK (e.g., Collins, 1976). This demand has continued and a preference for migrant workers in agriculture remains strong (Dench et al., 2006).

The structure of demand for migrant workers in UK agriculture has been described as dependent on the relationship between growers and retailers; recent changes in favor of retailers has meant a decline in margins for growers. Worsening terms of trade for the growers has been reflected in changing demands made of the workforce, which include more demanding working practices and lower wage rates. The characteristics of the workforce desired by the growers changed accordingly with greater premium put on reliability and the capacity and willingness to accept hard work and lower wages. Growers report that foreign nationals have provided these characteristics more readily, possibly due to their relative lack of security and greater vulnerability and the attraction of high earnings relative to home-country wages and immigration/work permit status (Rogaly, 2006; Frances et al., 2005).

The accession of CEE countries from 2004 to 2007 has changed the supply and character of migrant labor to western European agriculture and to southern EU states such as Greece (Kasimis and Papadopoulos, 2005). Progressive opening of labor markets in western Europe for workers from the new EU states has offered migrants a greater range of work and increasing confidence in asserting employment rights and some evidence has been forthcoming of possible shortages in the supply of seasonal agricultural workers from these sources (e.g., Topping, 2007). These changes have their own cascading effects illustrated by the re-focusing of the SAWS scheme in the UK to relate primarily to workers from Romania and Bulgaria who can only obtain work permits in the UK for agricultural labor. These two countries are the latest to join the EU; most western EU member states (including the UK) have imposed transitional |