Remote sensing and geographical information systems have provided tools for the monitoring, evaluation and better management of land use systems.

| Goals E |

Certainty A |

Range of Impacts 0 to +4 |

Scale L, R |

Specificity Tools with wide applicability |

Monitoring land use and land use change is an integral component of sustainable development projects (Janhari, 2003; Panigrahy, 2003; Verma, 2003). Remote sensing and GIS can cost-effectively assess short- and long-term impacts of natural resource conservation and development programs (Goel, 2003). They also have useful applications in studies of (Millington et al., 2001) urbanization, deforestation, desertification, and the opening of new agricultural frontiers. For example, these technologies have been used to study the spread of deforestation, the consequences of agricultural development in biological corridors, the impact of refugee populations on the environment and the NRM impacts of public agricultural policies (Imbernon et al., 2005). Modeling can extrapolate research findings and develop simulations using data obtained through remote sensing and GIS (Chapter 4).

3.2.2.1.2 Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

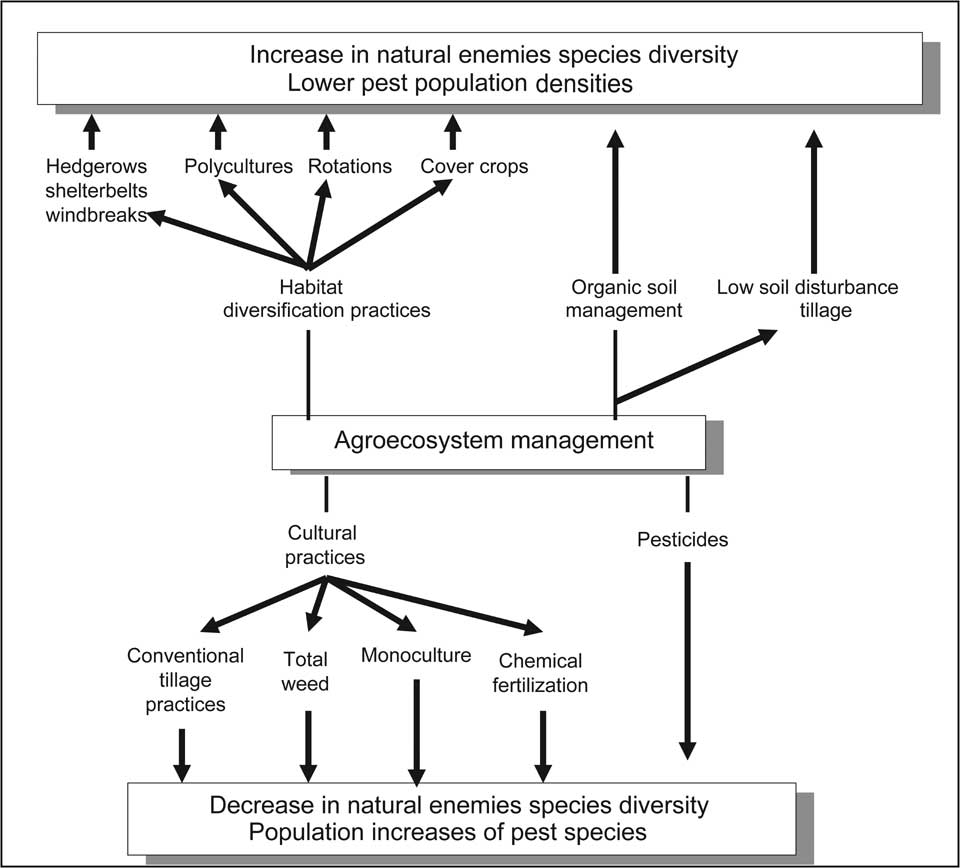

IPM is an approach to managing pests and disease that simultaneously integrates a number of different approaches to pest management and can result in a healthy crop and the maintainence of ecosystem balance (Abate et al., 2000). IPM approaches may include genetic resistance, biological control and cultivation measures for the promotion of natural enemies, and the judicious use of pesticides (e.g., Lewis et al., 1997).

The success of IPM is based on effective management, rather than complete elimination, of pests.

| Goals N, L, E |

Certainty B |

Range of Impacts +1 to +4 |

Scale N, L |

Specificity Wide applicability |

Success is evaluated on the combination of pest population levels and the probability of plant injury. For example, when climatic conditions are conducive for disease, fungicide has been found to be ineffective in controlling Ascochyta blight of chickpeas (ICARDA, 1986), but when combined with host resistance, crop rotation and modified cultural practices, fewer fungicide treatments can be both more effective and more economical. As an alternative to pesticides, IPM is most beneficial in high-value crops because of additional labor costs, but when the labor costs are low or IPM is part of a wider strategy to improve yields, IPM can also be of value economically (Orr, 2003). IPM can result in reductions of pesticide use up to 99% (e.g., van Lenteren, 2000). When compared to unilateral use of pesticides, IPM provides a strategy for enhanced sustainability and improved environmental quality. This approach typically enhances the diversity and abundance of naturally-occurring pest enemies and also reduces the risk of pest or disease organisms developing pesticide resistance by lowering the single-dimension selection pressure associated with intensive pesticide use.

IPM produces positive economic, social and environmental effects.

| Goals N, L, E |

Certainty B |

Range of Impacts +1 to +4 |

Scale M-L |

Specificity Wide applicability |

The past 20 years have witnessed IPM programs in many developing countries, some of which have been highly successful (e.g., mealy bug in cassava, Waibel and Pemsi, 1999). Positive economic, social and environmental impacts of IPM are a result of lower pest control costs, reduced environmental pollution; higher levels of production and income and fewer health problems among pesticide applicators (Figure 3-6). IPM programs can positively affect food safety, water quality and the long-term sustainability of agricultural system (Norton et al., 2005). Agroforestry contributes to IPM through farm diversification and enhanced agroecological function (Altieri and Nicholls, 1999; Krauss, 2004). However, the adoption of IPM is constrained by technical, institutional, socioeconomic, and policy issues (Norton et al., 2005).

Within IPM, integrated weed management reduces herbicide dependence by applying multiple control methods to reduce weed populations and decrease damage caused by noxious weeds.

| Goals N, E |

Certainty B |

Range of Impacts 0 to +3 |

Scale L |

Specificity Wide applicability |

In contrast to conventional approaches to weed management that are typically prophylactic and uni-modal (e.g., herbicide or tillage only), Integrated Weed Management (IWM) integrates multiple control methods to adaptively manage the population levels and crop damage caused by noxious weeds, thereby increasing the efficacy, efficiency, and sustainability of weed management (Swanton and Weise,

Figure 3-6. The effects of agroecosystem management and associated cultural practices on the biodiversity of natural enemies and the abundance of insect pests. Source: Altieri and Nicholls, 1999.