| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||

110 | IAASTD Global Report

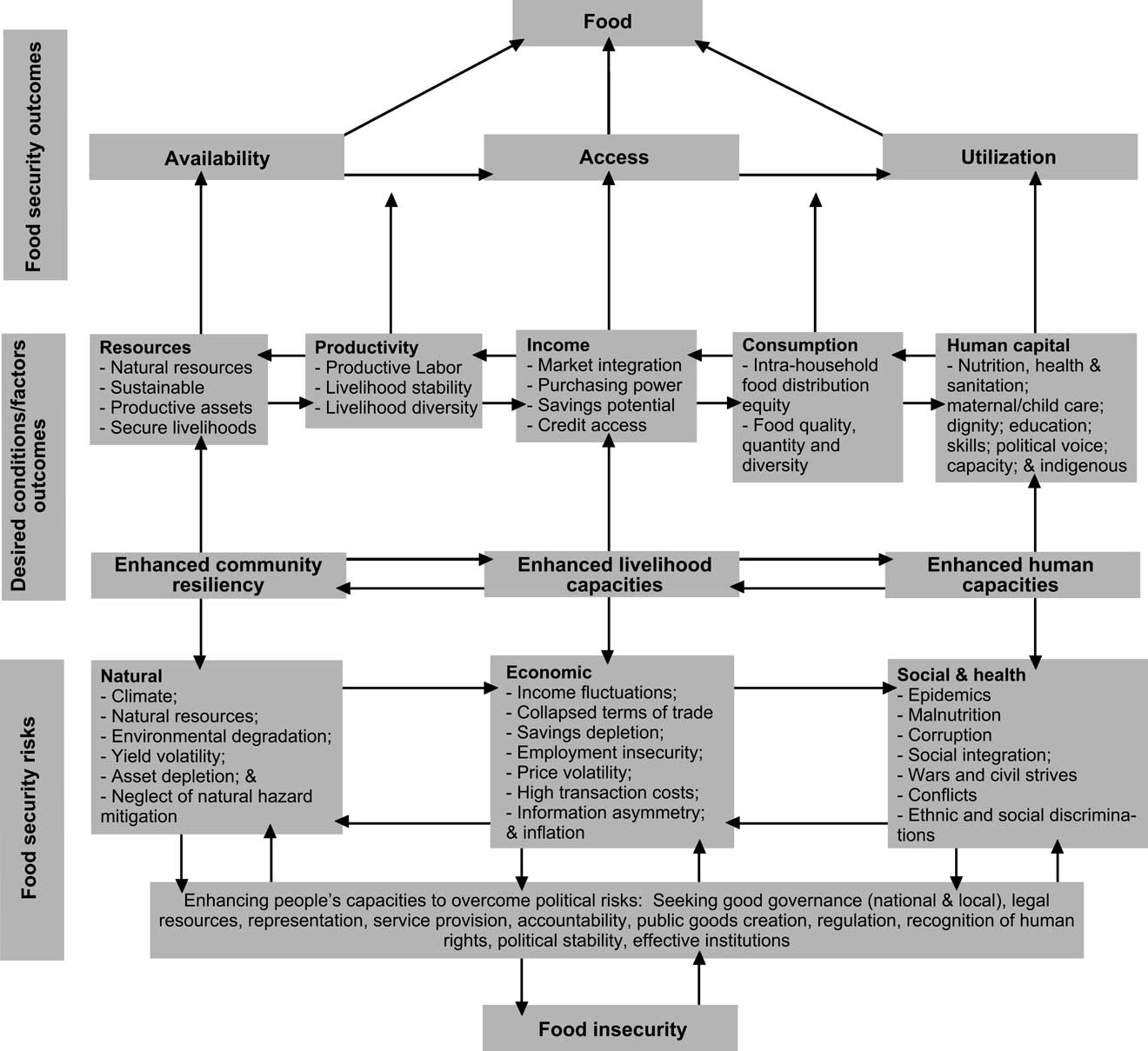

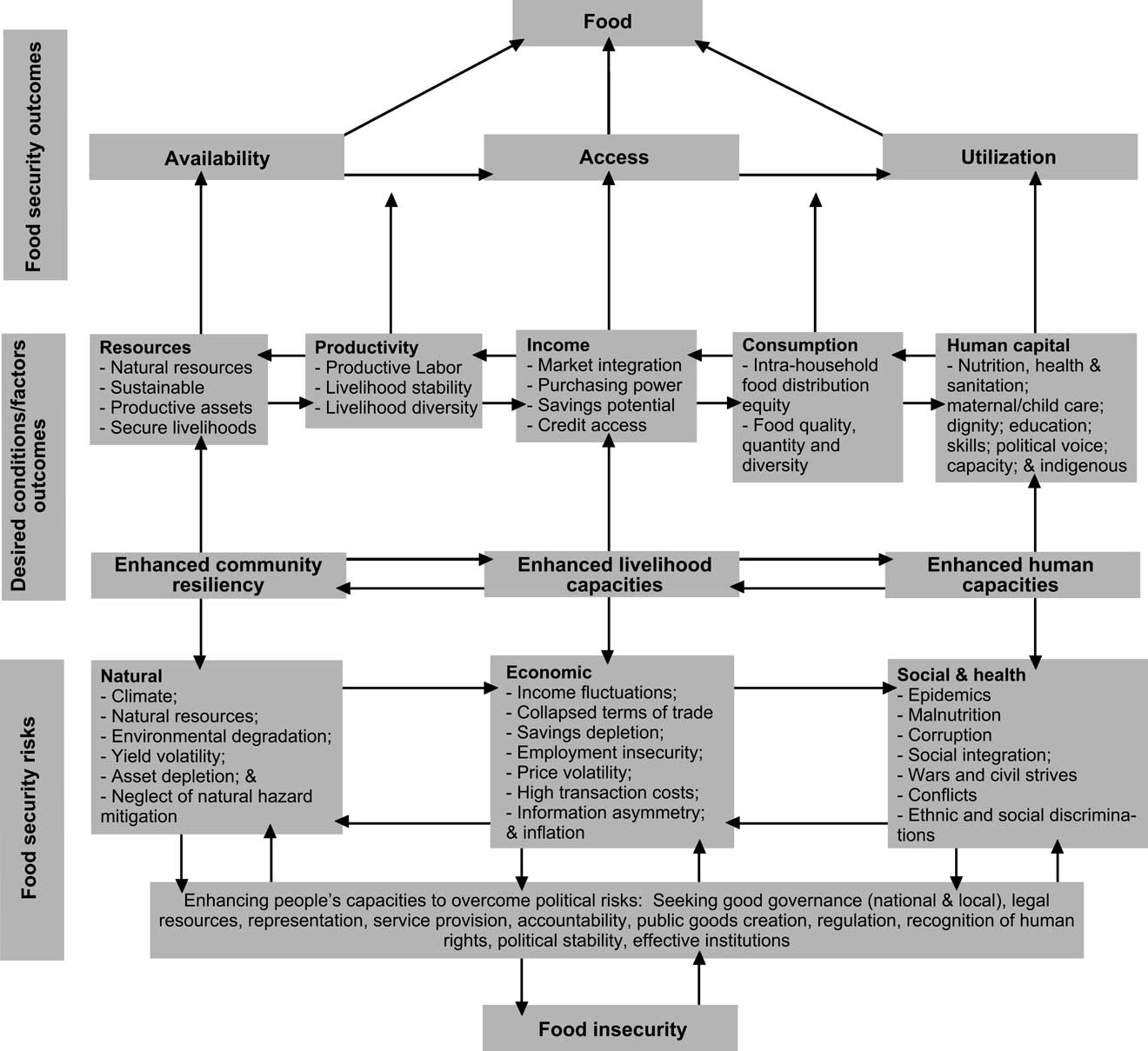

Figure 2-7. A framework for understanding food security. Source: Webb and Rogers, 2003.

|

Africa (FAO, 2001b; Lipton, 2001). In addition to other drivers (Johnson, 2000; Chopra, 2004), the failure of a Green Revolution in Africa (Crosson and Anderson, 2002) may partially be explained by the lack of improvement or worsening of the situation in Africa. Based on the Global Hunger Index (GHI)2 (Weismann, 2006), 97 developing and 27 transitional countries exhibit poor GHI trends; the malnutrition hot spots are in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where wars and HIV/AIDS exacerbate the situation. The commoditized monocropping characteristic of the globalized food system (GFS) has resulted in a narrower genetic base for plant3 and animal production (Knudsen et al., 2005; Lyson, 2005; Wilson, 2005) and in declining nutritional value (Welch and Graham, 1999; Kataki et al., 2001) and has negatively affected micronutrient reserves in the soil (Bell, 2004). A Mexican study, however, suggested that adoption of some improved varieties of maize had enhanced maize genetic diversity (Brush et al., 1988). Increasing and widespread micronutrient malnutrition has developed, 2 GHI captures three equally weighted indicators of hunger: insufficient availability of food (the proportion of people who are food energy deficient); prevalence of underweight in children 5 years old; and child mortality ( 5 years old mortality rate). 3 Wheat, rice and maize account for the majority of calories in human diets. |

affecting millions of people in industrialized and developing countries alike (Welch and Graham, 1999; Khush, 2001) with quantifiable costs through compromised health resulting from reduced productivity and impaired cognition (Welch and Graham, 1999). However, recent improvements are noted in some parts of the developing world (Mason et al., 2005). Meanwhile, elements of the GFS, for example, subsidies of commodity crops such as corn in the US (Fields, 2004), have contributed to often radical and rapid changes in dietary patterns characterized by an excess of highly refined carbohydrates, sucrose, glucose and syrups (ingredients in fast foods) and animal fats, with a parallel decline in intake of complex carbohydrates (Tee, 1999; Fields, 2004; Young, 2004). These changes, combined with a decline in energy expenditure associated with sedentary lifestyles, motorized transport and household domestic and work place labor-serving devices (Young, 2004) have resulted in the emergence of obesity and other dietary-related chronic diseases afflicting both the affluent as well as the low income population in industrialized and developing countries (Tee, 1999; Fields, 2004; Young, 2004). This paradoxically coexists with undernutrition (Young, 2004), signifying growing imbalances and inequities in food systems. In the 1980s, food production shifted toward products that were convenient and served ethnic and healthbased preferences. This shift has changed the structure of |

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||