| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||

Context, Conceptual Framework and Sustainability Indicators | 7

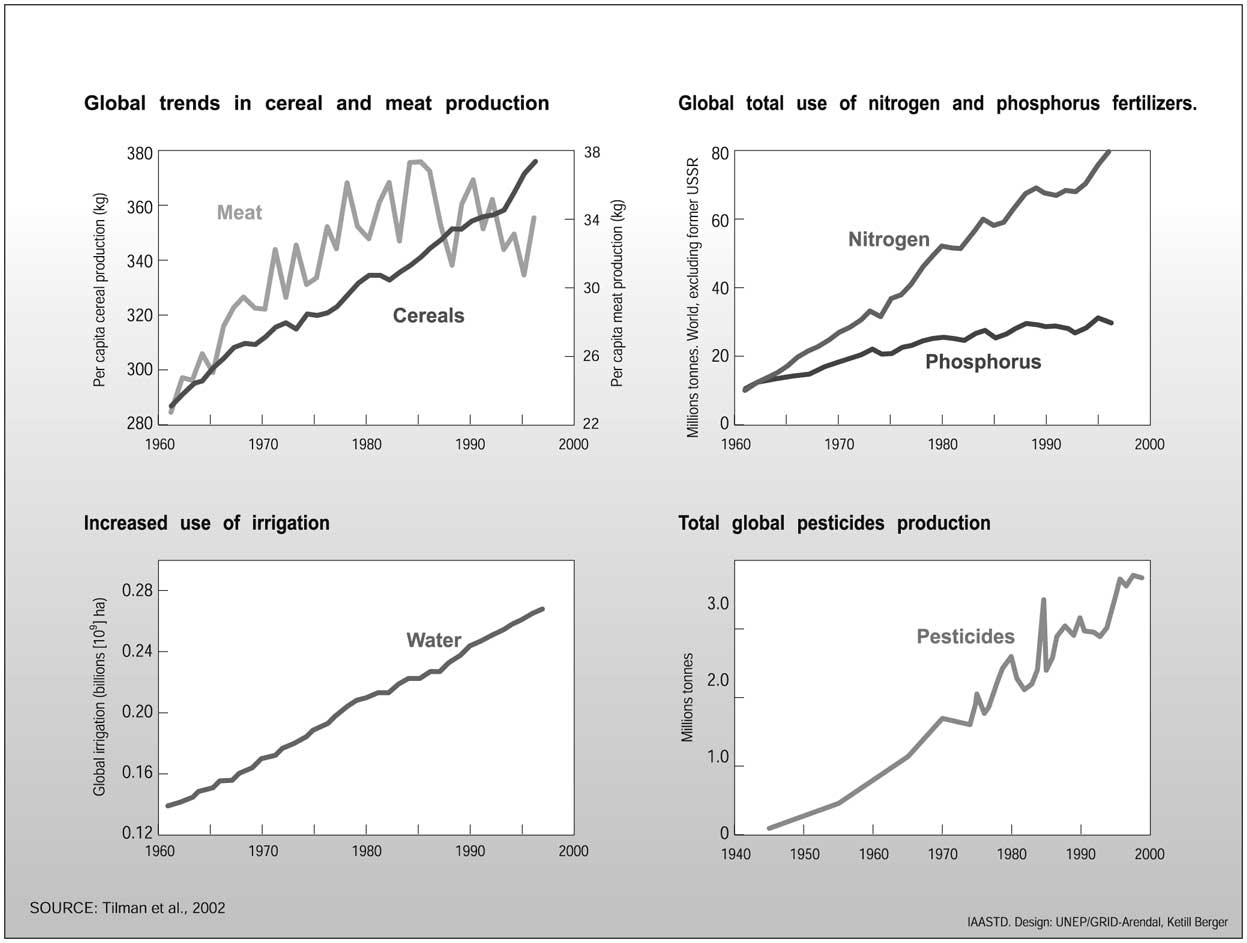

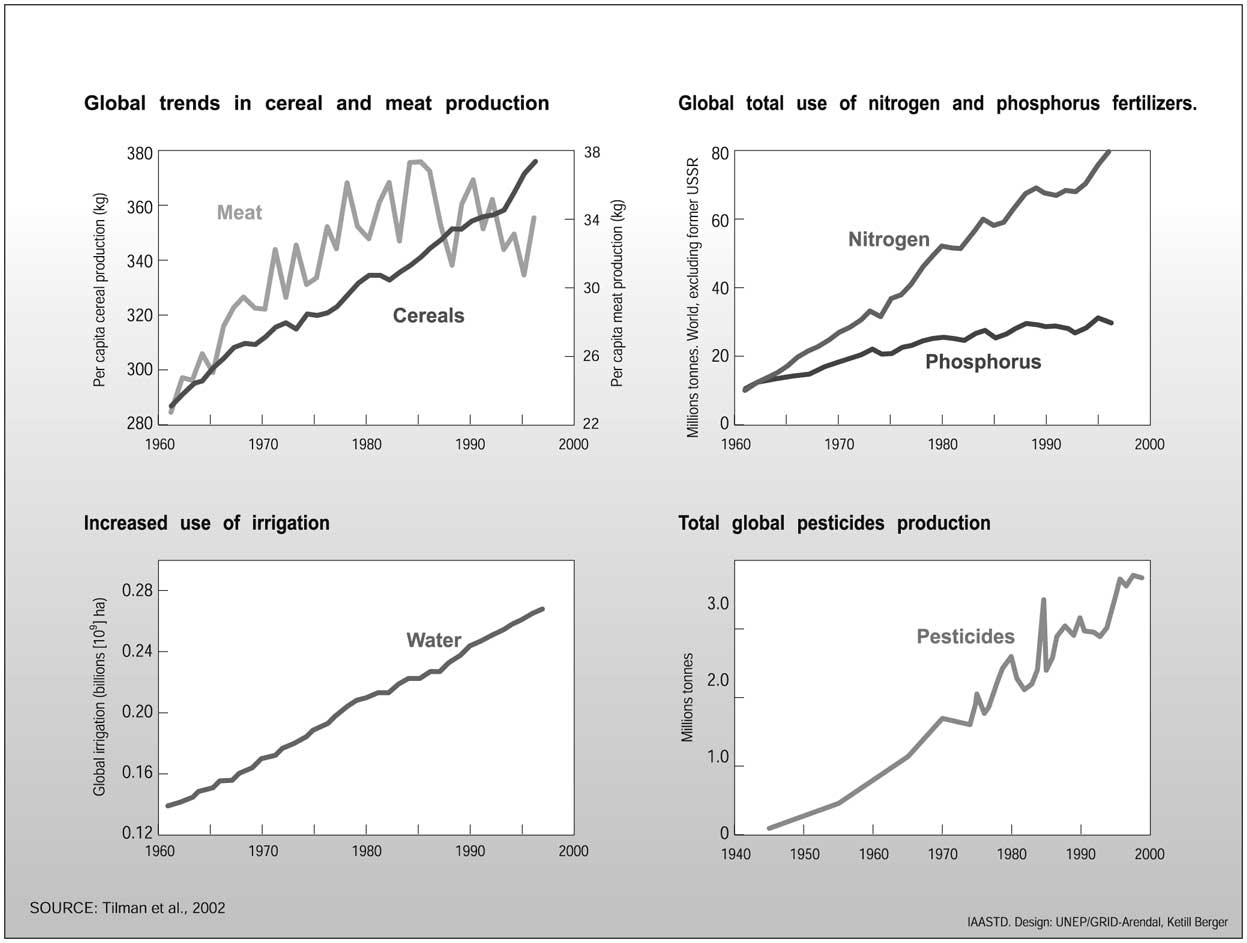

Figure 1-2. Global trends in cereal and meat production; nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer use; irrigation, and pesticide production.

|

tion in the production and trade of agricultural goods. Globalization has resulted in national and local governments and economies ceding some sovereignty as agricultural production has become increasingly subject to international agreements, such as the World Trade Organization's Agreement on Agriculture (WTO, 1995). The progressive expansion of commercial-industrial relations in agriculture has put further strain on many small-scale farmers in developing countries who must also contend with direct competition from production systems that are highly subsidized and capital intensive, and thus able to produce commodities that can be sold more cheaply. Newly industrialized countries like India have increasingly subsidized inputs in agriculture since the early 1980s (IFPRI, 2005). Competition, however, does not only originate in subsidies from agricultural policies of richer countries; it may also derive from large entrepreneurial holdings that have low production costs, which are primarily but not exclusively found in developing countries. Three phenomena related to globalization are specific for a number of countries: the growing impact of supermarkets and wholesalers, of grades and standards, and of export horticulture, have substantially favored large farms (Reardon et al., 2001, 2002, 2003) except when small farmers get special assistance through subsidies, micro-contracts or phytosanitary programs (cf. Minten et al., 2006), for example. A steady erosion of local food production systems and eating patterns |

has accompanied the net flow of food from poorer to richer countries (Kent, 2003). While average farm sizes in Europe and North America have increased substantially, in Asia, Latin America, and in some highly densely populated countries in Africa, average farm sizes have decreased significantly in the late 20th century, although they were already very small by the 1950s (Eastwood et al., 2004; Anriquez and Bonomi, 2007). These averages conceal vast and still growing inequalities in the scale of production units in all regions, with larger industrialized production systems becoming more dominant particularly for livestock, grains, oil crops, sugar and horticulture and small, labor-intensive household production systems generally becoming more marginalized and disadvantaged with respect to resources and market participation. In industrialized countries, farmers now represent a small percentage of the population and have experienced a loss of political and economic influence, although in many countries they still exercise much more power than their numbers would suggest. In developing countries agricultural populations are also declining, at least in relative terms, with many countries falling below 50% (FAO, 2006a). Although, there are still a number of poor countries with 60-85% of the population working in small-scale agricultural systems. The regional distribution of the economically active population in agriculture is dominated by Asia, which accounts for almost 80% of the world's total active population, followed by Africa with 14%. Although the overall number |

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||