where reefs had been degraded exemplifies the increase of vulnerability as a result of unsustainable human activity (IUCN, 2005).

Natural ecosystems often have had to bear the brunt of intensification in agriculture. The degradation of forests, grasslands, coastal ecosystems and inland waters threatens their services to, and thus the long-term productive capacity of, agroecosystems. It is known that in many cases agricultural activities have depleted natural resources (forests, soil, water) to an extent that has resulted in net productivity losses; these developments are caused by a wide range of drivers. In other cases (e.g., rainfed agriculture or sustainable soil conservation) agricultural practices have been operated by generations of successive farmers in a sustainable way.

Natural resources and their management

Forestry.Agriculture has had an intimate and productive relation with forests: many historical and contemporary farming systems are built partly on that relationship. Swidden agriculture in tropical areas, for example, uses forests as a means of soil and nutrient restoration.

Agroforestry and home garden systems are ways of combining trees and other species with crop production or animal husbandry. Up to the present, forests and agroforests have played an important role in contributing to the food security of a large part of the world's food insecure people. They provide products (timber, fuelwood, food, and medicines), inputs for crop and livestock production (fodder, soil nutrients, and pollination) and services (watershed protection, climate regulation, carbon storage, and biodiversity conservation) (FAO, 2006a).

Some 350 million of the world's poorest people are considered to be largely dependent on forests for their living, including for food production (WCSFD, 1999). A majority of farmers manage some trees on their land, or benefit from forests adjacent to their land, often for environmental services (e.g., to shelter or shade homes, crops and livestock, or for soil conservation), as well as for diverse products (such as fuelwood and fruit) (Scherr et al., 2004; Molnar et al., 2005). Approximately 1.5 billion people use products from trees as key elements of their livelihoods (Leakey and Sanchez, 1997).

Deforestation has been identified as a major problem facing forest resources. The expansion of agriculture in its many forms at the expense of forestland is one of the factors contributing to deforestation, though not the only one. The conversion of forest to another land use or the long-term reduction of the tree canopy cover below the minimum 10% threshold is one definition of forestry. The rate of deforestation is proceeding at 13 million ha per year (FAO, 2007a).

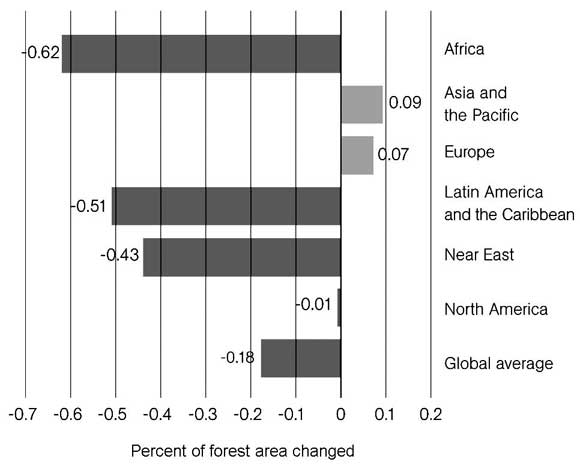

Recent estimates show that forests cover about 31% of global land surface (FAO, 2007a). Since pre-agricultural times, forests have been reduced by 20 to 50% (Matthews et al., 2000). Patterns of forest management and use vary across the globe. Thus, for instance, while the last two and a half decades have seen an increase in forest area in industrial countries, developing countries have on average witnessed a decline of about 10% (FAO, 2007a; Figure 1-17). An increasing trend is also the rapid expansion of mixed forest/

agriculture zones encroaching on formerly intact forest areas. 80% of the fiber and fuelwood production is derived from primary and secondary growth forests and therein lies the importance of management of this important resource. In addition to fiber and fuel, forests provide a range of ecosystems services. Forests make up two thirds of the more than 200 ecoregions identified by WWF as outstanding representatives of the worlds' ecosystems that include important endemic bird areas and more than three quarters of the centers of plant biodiversity (Olson and Dinerstein, 1998). Forest soils and vegetation store about 40% of all carbon in the terrestrial biosphere. However, due to deforestation rates that exceed growth, forests are currently a net source of atmospheric carbon. Loss of forest cover in watersheds has secondary effects on water resources through increased erosion, and alteration of water quantity and possibly floods. It has been estimated that roughly 0.75 ha of forest is now needed to supply each person on the planet with shelter and fuel (Lund and Iremonger, 1998).

Biological corridors play an important role in mitigating incidental or secondary effects. Thus, in some regions in Central America, using local and foreign funds, international organizations, governing institutions and rural committees are working to connect natural reserves by planting native tree species in deforested areas. These new green spots will open routes for the safe migration and mating of wild animals, as well as preserve the wild and native flora.

Grasslands

Grasslands are mostly associated with drylands where plant production is limited by water availability-the dominant users are large mammals, herbivores including livestock, and cultivation. Drylands include cultivated lands, scrublands, shrublands, grasslands, semideserts, and true deserts (MA, 2005c). They are, as their name implies, natural landscapes where the dominant vegetation is grass. Grasslands usually receive more water than deserts, but less than forested regions. Worldwide, these ecosystems provide livelihoods for nearly 800 million people. Grasslands are also a source of

Figure 1-17. Annual net change in forest area, 2000-2005. Source: FAO, 2007a.