| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||

78 | Latin America and the Caribbean Report

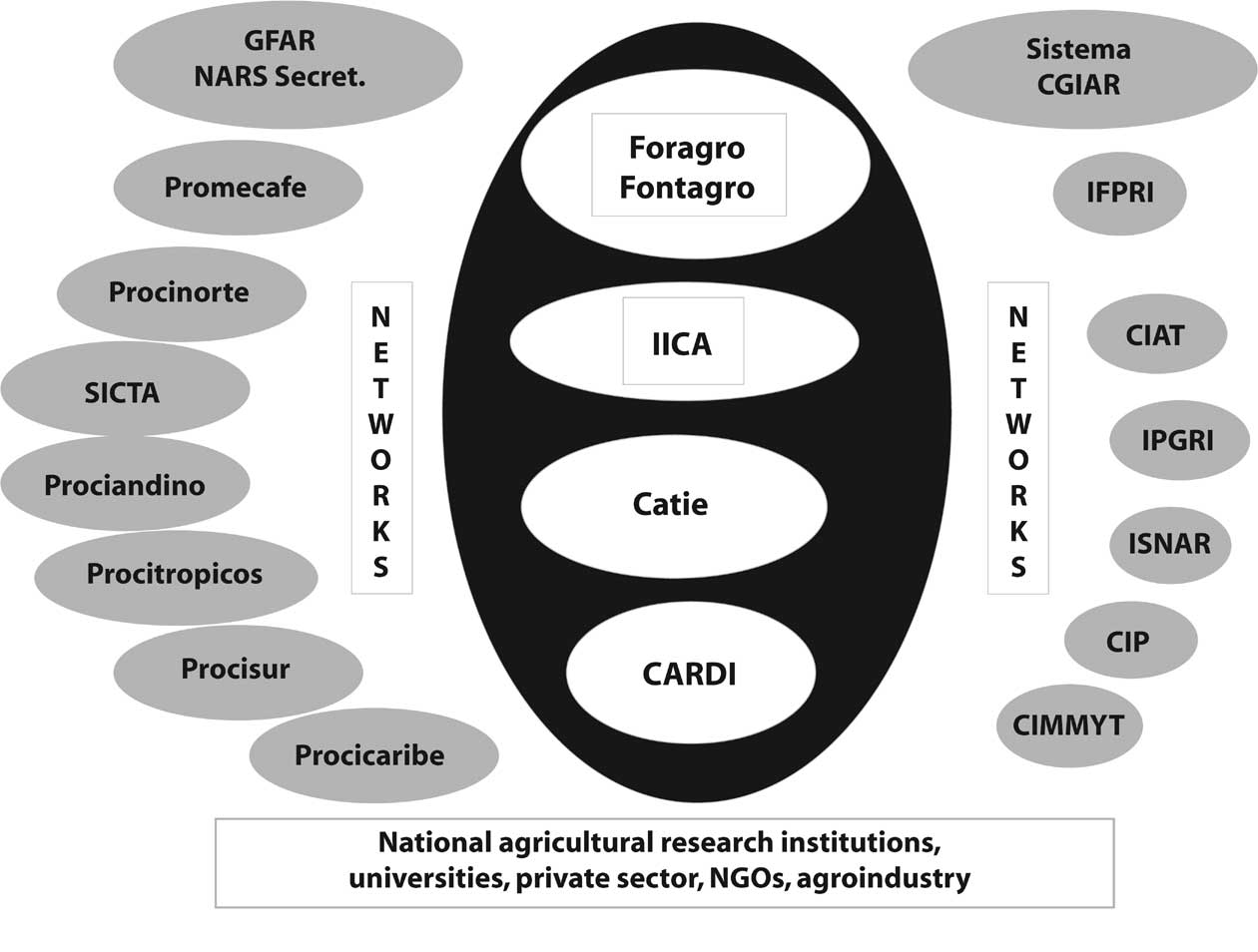

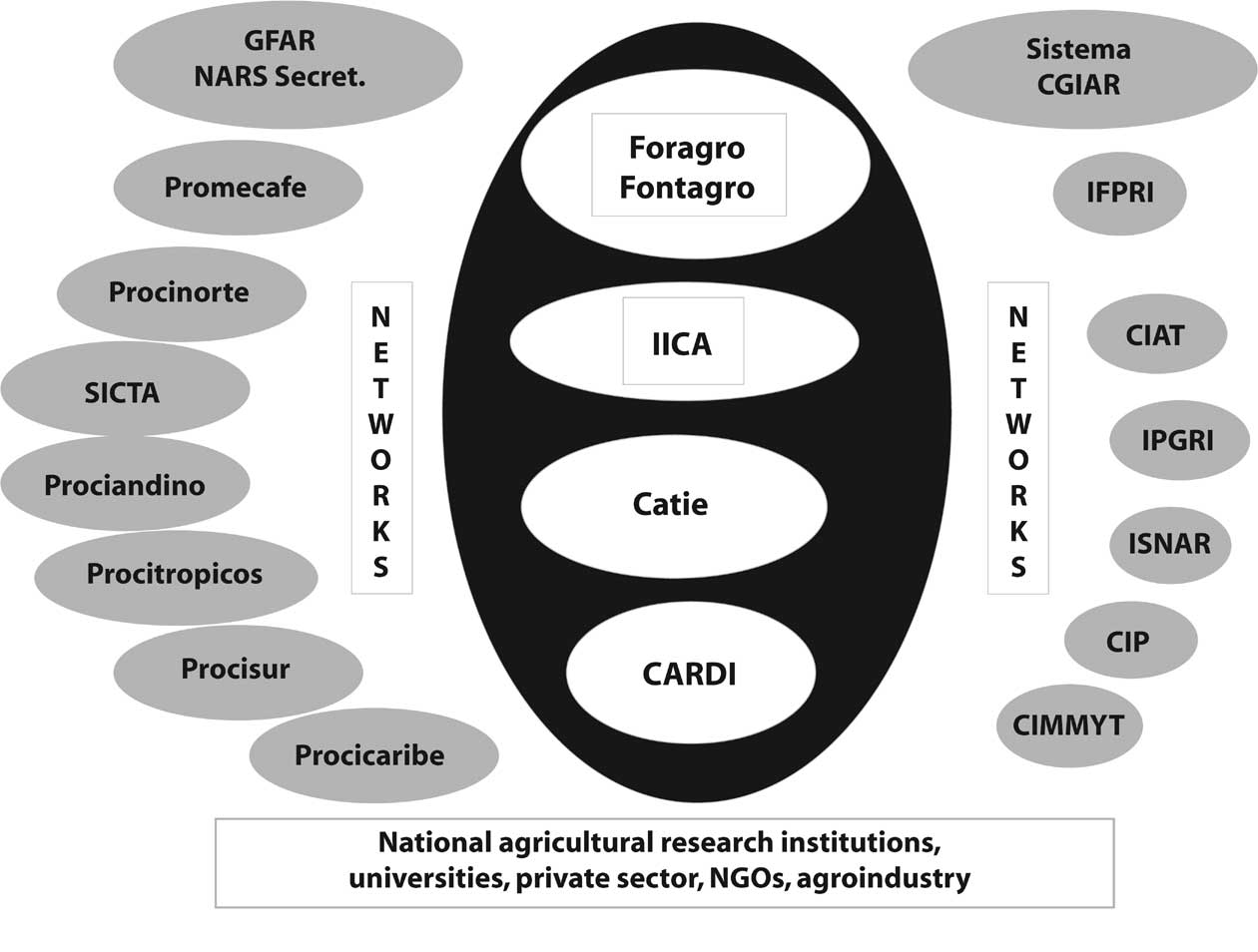

Figure 2-1. Regional agricultural technology innovation system for the Americas. Source: Ardila, 2006

|

and AKST system institutions can be attributed to regional contrasts within each country, decision-making of a political nature, and limited social participation. They also reflect a trend toward privatizing research, technical assistance, and technology transfer to small and medium-scale producers, as a result of administrative decentralization, structural adjustment, and market liberalizationall phenomena that have accelerated in the last two decades (Quiroz, 2001). Several countries have attempted, through public policies, to develop production systems that break the cycle of exclusion and environmental degradation, and also incorporate a gender perspective and an indigenous and Afro- American worldview. However, much remains to be done to ensure the real participation of those stakeholders in decision-making at the local level (Dirven, 2001). Rural societies are also becoming more complex. More interactions between different types of stakeholders blur the boundaries between the rural and the urban. New scenarios are emerging, created by the demands of the various actors and their respective local organizations. With regard to the AKST system, local development processes pursued by communities, either independently or in partnership with universities, foundations, corporations, cooperatives, producers associations, and both national and international non-governmental organizations, offer the possibility of reappraising traditional knowledge, developing greater negotiating power, improving territorial management, and strengthening claims for access to land. This is evident in various social movements such as the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico; the Landless Peasants Movement in Brazil; and the claims of the Mapuche indigenous |

people in Chile and Argentinaall of which have had local impact as well as regional and international repercussions on the design of a new paradigm regarding AKST at the Latin American level. Most Latin American states have not yet resolved their agrarian problem, one that affects their respective societies, particularly local rural sector organizations. However, this phenomenon is no longer associated exclusively with the rural milieu, but has also spread to urban areas (Machado 2004). In spite of some isolated experiences, new advances in AKST involving bioelectronics, bioinformatics, and biotechnology have not been widely adopted by local organizations or campesino farmers. Moreover, no reconciliation processes have emerged to take advantage of their positive aspects (Amaya and Rueda, 2004; León et al., 2004). 2.1.2 National organizations LACs AKST system is made up of a vast network of public, private, and third sector institutions in the various countries that have generally had a major impact, reflecting the relative importance of agriculture to the region. Within this system, the national public agricultural research institutes, generally known as NARIs (or INIAs in Spanish), have a long historymany were created more than half a century agoand have played a significant role in generating technologies for this sector. Just as LAC is a heterogeneous geographic area, the NARIs of the different countries also display varied characteristics. Some enjoy a high profile and receive the major share of their countrys investment in agricultural science |

| Previous | Return to table of contents | Search Reports | Next |

| « Back to weltagrarbericht.de | ||