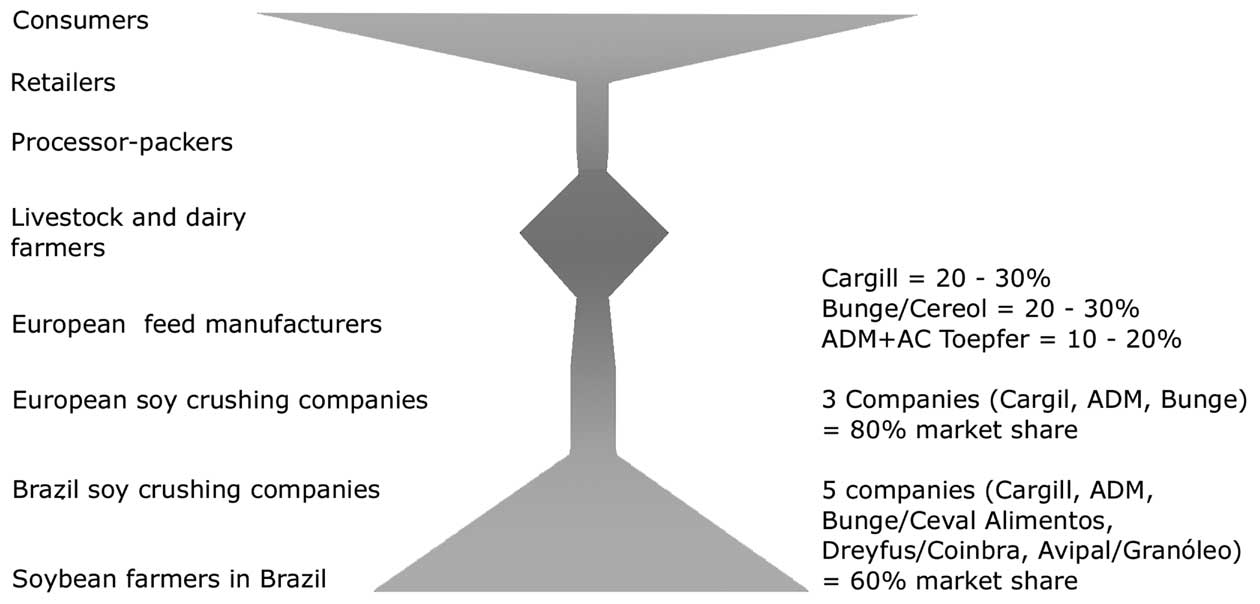

Box 1-10. Integration of the soybean food chain in Latin America: From the producers to the consumers |

||

Only a small fraction of the soybean is consumed directly as food

for humans; the rest is processed mainly to produce oil for the

food industry and as high-protein tablets for animal feed.

In Brazil, it is estimated that the soybean crop employs one million persons directly and that the soybean industrial complex employs some five million people. In the 1980s soybean production shifted from the south and southeastern regions, with small and medium producers (average 30 hectares) to the region of Mato Grosso and Goiás, including the cerrado region, with an average farm size of 1,000 hectares. A single company, Andre Maggi, has 150,000 hectares and produces one million tons of soybean per year. The consequence of this concentration in farm size has led to an increase in |

rural unemployment and food insecurity, spurring migration to

the cities. The soybean market is characterized by a high degree of integration, as large corporations control the production, processing, and marketing, in both exporting and importing countries. The four corporations that dominate soybean market, Bunge, ADM, Cargill, and Dreyfus, also process soybeans. Cargill claims to be the largest company worldwide engaged in the extraction of soybean oil. Cargill is also the largest exporter of vegetable oil and soy protein in Argentina. Dreyfus is the third leading company in terms of volume that processes vegetable oil in South America, and is the owner of and operates the giant port on the Paraná river and the giant company General Lagos crushing plant. |

|

Soybean feed “Bottleneck” from Brazil to Europe. Source: Vorley, 2003 |

||

trade and access to the industrialized countries’ markets for

goods and services (Vorley, 2003). 1.6.2.4 Sociocultural characteristics |

There are other sociocultural aspects that determine

differences within this productive system and set it further

apart from commercial agriculture. The family develops socially

and economically in a milieu marked by geographic

isolation distinct from the urban-industrial sector. Many of

its members have a common socio-historical development

and families share traditions and customs that are determinant

in their lives in terms of relationships and production.

In this sociocultural setting tradition is the dominant institution

in relationships and exchanges. In that rural milieu

there is a close relationship between the degree of isolation

and traditional patterns. These aspects define more family farming of the peasant and indigenous type, where the peasants constitute a subculture, but this peasant pattern in countries such as Chile, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay differs from that of other regions of Latin America (Peru, Guatemala, Mexico and Bolivia, among others), in which the indigenous cultural characteristic is even more determinant, in some cases to the point of having their own cultural traits (Rojas, 1986). Another fundamental element that identifies this system socioculturally is belonging to a local community in which |