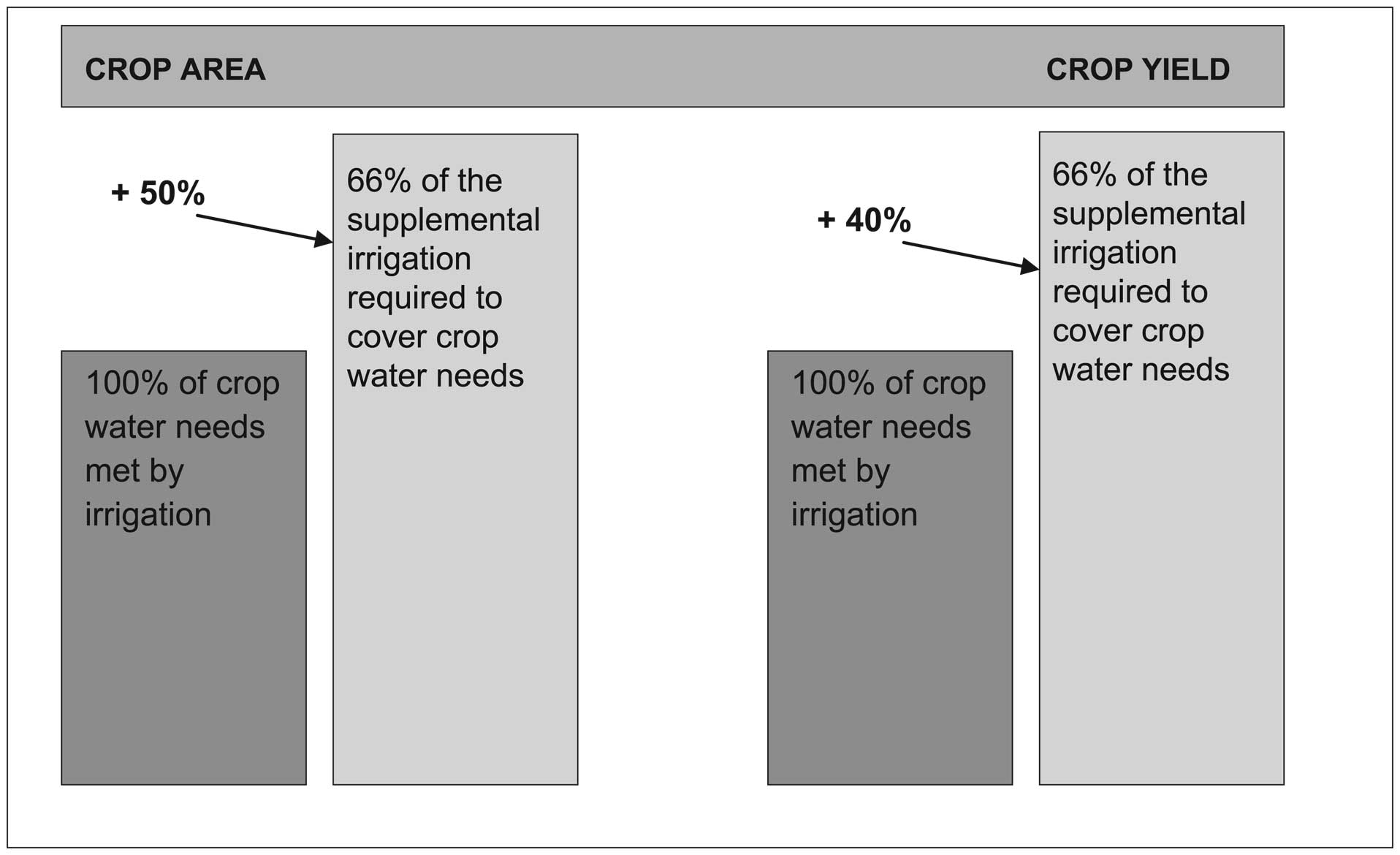

fully satisfying crop water requirements, allows achieving considerably the higher total crop yields and water productivity as compared to using the water for full irrigation on a smaller area (Oweis and Hachum, 2001).

In some of the richer countries of CWANA, high-tech irrigation systems may be used to reduce water use for irrigation; however, low-cost irrigation systems are in general of greater need in the region. Besides improving the performance of gravity irrigation systems, such as basin, border or furrow irrigation, and low-cost sprinkler systems, in particular portable hand-move systems, great potential exists for low-cost micro-irrigation systems (SIMINetwork, 2006). However, proper irrigation practices (see Aillery and Gollehon, 2003) are prerequisite for efficient water use with any irrigation system; practices worked out in developed countries such as the United States may well be suited or adapted to conditions prevailing in the water-scarce environments of CWANA. Modern tools for improved irrigation scheduling such as crop simulation models fed with actual climatic data and coupled with GIS can greatly improve water productivity and help manage water resources for irrigation even at large scales, such as in the Jordan Valley or Egypt.

It is important to raise awareness that by using less water more efficiently high yields of good quality are achievable. Education and training are extremely important to raise understanding of how much water a crop requires and how water may be managed more efficiently, avoiding the negative effects of overirrigation. Socioeconomic factors such as awareness and experience, but also the financial capacity of the farmer, access to affordable inputs and knowledge regarding irrigation systems and their maintenance and scheduling are “soft” factors that are as important for productive water use in irrigated cropping as technological aspects.

However, even the most sophisticated irrigation and scheduling practices are of little value if water organization,

allocation and distribution systems are deficient. In many CWANA countries water is allocated through public entities. Several excellent examples of water allocation systems, such as in the Jordan Valley, may show the way toward managing water more productively at the project or perimeter level. Establishing water user associations that jointly organize and manage water allocation and distribution may represent another way to facilitate productive water use considerably and at the same time empower local populations while relieving public institutions.

Salinity represents a major threat to irrigated agriculture in most areas of CWANA because evapotranspiration generally exceeds precipitation to a great extent—as early as in the third millennium BC, the Sumerian cities of Mesopotamia crumbled, partly because of salinization due to poorly managed irrigation. Proper irrigation management and availability and maintenance of suitable drainage systems are keys to avoiding land degradation due to salinity. Particularly in cases where unconventional water sources are used for irrigation, such as drainage of brackish water, management practices have to consider the considerable threat of salinity. Strategies and technologies to avoid salinization are sufficiently known.

Rendering water use more efficient in irrigated agriculture is not only important for increasing crop productivity in dry areas (and thus revenues and livelihoods of irrigating farmers; see Lipton et al., 2003). Saving water in agriculture frees up substantial water resources that may be used in other sectors and activities, which is important for overall development of a society. Therefore, IWRM has become a key principle, in particular with regard to irrigated agriculture.

In conclusion, numerous AKST options to use scarce water resources in CWANA more productively and efficiently in irrigated agriculture already exist. It is important to recognize that in addition to technical improvements, organizational and political considerations, plus increased

Figure 5-1. Increasing wheat yields in Syria by reducing irrigation: The effect of deficit irrigation on yield and water productivity. Source: Oweis and Hachum, 2001.